The Coens portray various forms of disingenuous malice within the American entertainment industry through two powerhouse lead performances.

Clearly, a lot has been written about Barton Fink as a metaphor for the Holocaust. None of which I have read nor had read before seeing it, rather, I’d discovered it myself over the course of its runtime, slowly gathering the (fairly obvious) clues the Coens were leaving behind in scenes that at face value were about the pressures of creating art in a strict labour industry, but simultaneously, settled beneath that wrinkled, bog-standard Hollywood envelope, came to be made known as direct allusions to its grand, histrionically spoken allegory; that of the endless psychopathy of Nazism (not to speak of fascism in general), and its direct, immediate parallels with serial violence.

It’s a simple message, really; but the Coens deliver it with such an adept grasp of poetry and religious showmanship that it’s hard not to be swept up in its symbolism without considering it to be anything less than profound, a demanding piece of work whose ambiguity (and seemingly, the Coens’ own prohibitive attitudes towards any in-depth analysis) only serves to generate more curiosity within the viewer’s mind about what it all means, what the story can represent to each audience member watching. It’s clearly the most well-composed work the Coens have ever done (the Jack Litner work-in-progress scene alone is a mini-masterpiece), having them ambitiously reach and flawlessly harness all the beautiful personification one could hope for in a narrative that is so innately allegorical, creating their most tightly compacted and intellectually stimulating work, quite possibly, to date.

Our first indication as to what underpins this narrative is the stereotypical Jewishness that’s implied by Fink’s name and wardrobe, a choice no less subtle than the German and Italian surnames ‘Mundt’, ‘Mastrionatti’, and ‘Deutsch’ (for Goodman and the two hostile detectives) being chosen for the external forces that oppress him, one through his ideologically justified rampages and the others through superficially organized repression based in entirely fabricated accusations. Their behaviour exhibits a definite resemblance to the public coercion employed by the Nazi government, whereas Mundt’s lone genocidal binge reflects the hard state power that follows, summoning a supernatural inferno at his own discretion to burn away all that he feels is offensive to his delusional conceptions of liberty.

C’mon, Barton, you think you know pain? You think I made your life hell? Take a look around this dump. You’re just a tourist with a typewriter, Barton, I live here, don’t you understand that? And you come into my home… and you complain that I’m making too… much… noise.

Mundt’s liberty is all-encompassing, to him it means rejecting any possible obstruction of his freedom of speech and to refuse to accustom himself to his fellow man in any way whatsoever, whether it be by lowering the noise he creates in a hotel that he considers to be his home and his home alone or by accepting that the ubiquity of persons unlike him in his homeland is just as valid as his residence there. He blames the cruelty inflicted upon him, the conditions he lives under, on the identically repressed around him, pointing to them as the catalysts for what holds him back from plain enjoyment of life; he’s a man who feels as though the very presence of a human being who is different from him, one who asks for simple accommodation, is a parasite on his comfortable subsistence, a manacle on his right to act without separating from what he believes to be natural and good. He is Nazism as indoctrinated into “the common man”, a crushed labourer who’s been deceived into believing that the source of his poverty is a particular hypothetical person whose foreignness becomes an easy-to-work cloth from which to sew an artificial enemy; in this case, a Jew, but the villains of fascist narratives can be stitched from many fabrics.

From Fink’s perspective, he’s also fascism as its image mutates over time, when its presentation of itself as down-to-earth gains considerable strength, before soon enough, the piecemeal degradation from charisma into psychopathy takes place as horrors occur all around, and it becomes apparent that hate has consumed every facet of society. As the world overturns around him, the walls melt and fire dominates his path, and the simple massiveness of the atrocities that now run rampant impresses upon his psyche, breaking him completely with their power. The allure of an ideology allegedly based in the value of “the common man” is broken, with charm revealing itself as the brutality it had always been underneath. What the Coens realize is that rarely, if ever, are the two appearances different things.

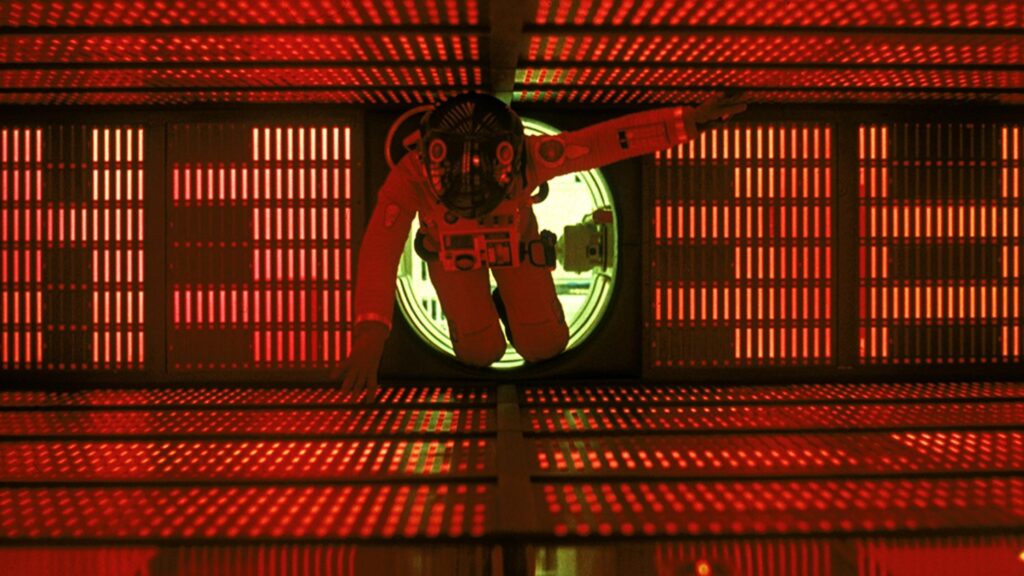

Barton Fink never lets up with its intensity; even its quiet moments have an air of psychological torment cast over them, rearing new tension separate from the utter mania that the Coens are so adept at presenting. Roger Deakins, in one of his earliest notable credits, beautifully wields every cinematographic fibre in his mind like a weapon, effortlessly harmonizing with the harsh energy brought out by both the actors and directors with his precise construction of shots that range from uncanny to playful in a second; his ghostly hovering from Barton’s bed to the inside of dingy, echoing hotel pipes is masterful, an exemplary illustration of wordless storytelling that remains deeply eerie all the way through its creeping rove, telling us everything we need to know about Karl Mundt before we ever hear a whisper of his insanity.

Turturro brings out a brilliant performance both inhibited and immodest, perhaps overshadowed on first viewings by the monstrous ardour unleashed by Goodman in the final act, but no less expertly rendered through his uninterrupted manifestation of the character; at times, he moves and speaks in direct opposition to tepidness with an animated earnestness only possible in an artist, when outlining his ideas, he serenades with a selfish passion, paradoxically assuring the value of the stories that proletarians have to tell while ignoring those that are emerging right in front of him, while otherwise, in those moments where he’s forced to engage with the daily blather and trifles of life, he mutters timidly with the social awkwardness of a teenager, both as a struggled reaction to the traumatic incidents he’s just recently experienced, and as a push away from the tedium that he finds in unexceptional day-by-day insipidity.

That insipidity is what he fights constantly with his writing, undertaking the struggle to contradict the innocuous, artless brush strokes that comprise Hollywood’s lifeless make-up and tell stories that embrace the genuinity of every John Smith he sees at the bottom of the societal hierarchy; or, at the very least, so he believes in his infancy as a recently successful playwright, when as a bourgeois intellectual, he can only ever insist upon their value while simultaneously failing to understand them on the intimate level he believes he does, hence his disastrous strike with writer’s block when he’s forced to forge a narrative surrounding one. It’s only at the point that he learns of Mundt’s true nature that he’s able to devise something, and even then, it’s a fable informed by his own deep-rooted biases on the violence of poor people, one that equates fascistic cruelty with the innately brutal tendencies of “The Burlyman”.

Hollywood doesn’t want to hear it regardless. Its shallowness is too intrinsic in its character to confront stories that are even slightly based in degrees of humanity, so any that arise are instantly fought against by the vapid superstructures that comprise it, as though any blow with weighted nuance would instantly knock down its foundations built in artifice. Jack Litner pridefully values arbitrary status symbols that only serve to justify his autocratic dictation, ones that he admits were literally fabricated for him (both by nepotism and by the Wardrobe Department of Capitol Pictures) and that remind Barton of the tyrannical stranglehold that ruling class authorities hold to wash away the severity of the horrors that occur on their beck and call; the atrocities he experienced are actively censored as they pose a threat to the continued control over a narrative insisting total prosperity, the genocides of fascism being hidden from the public so that they may be fed simplistic fictions of good triumphing over evil.

Sounds like a state-controlled media system if there ever was one.

Thus, what the Coens delineate is that Barton is left hopeless in combatting the cruelty around him, that his promise to help those he pities at the substratum of society is forcibly left unfulfilled because of the machines that punch down on his ability to do so. All he can write as a slave to the larger system are abstract, ungrounded hero’s journeys that have no bearing on the ideas that he sincerely hopes to present, his capacity to resemble humaneness in creating art (though his ideas were already heavily steeped in philistine prejudices) now totally vanished, his toil as a labourer himself gone wasted because of the strict confinements constructed by absolutist powers, and his experiences as a Jewish person having undergone unimaginable horrors urgently erased by those same powers to uphold their myth. He is defeated, so he wanders, not because he is lost, but because he has been totally trapped in the drudgery of labour subjugation — enclosed within one city, within one hotel, by a desk in front of an immobile image of a woman looking far out onto raging waters.

And a soaring bird drowns.