Miyazaki’s first and last biopic is as epic as his fantasies, but held hostage by the political baggage of fascist history.

Better yet, what would be an Oscar bait movie had Hayao Miyazaki not directed it. With the benefits of both his beautifully majestic and beautifully haunting visuals, Miyazaki magnifies every emotion (that would otherwise be lost in mundane direction) so significantly, his audience feels each one just as much as the protagonist.

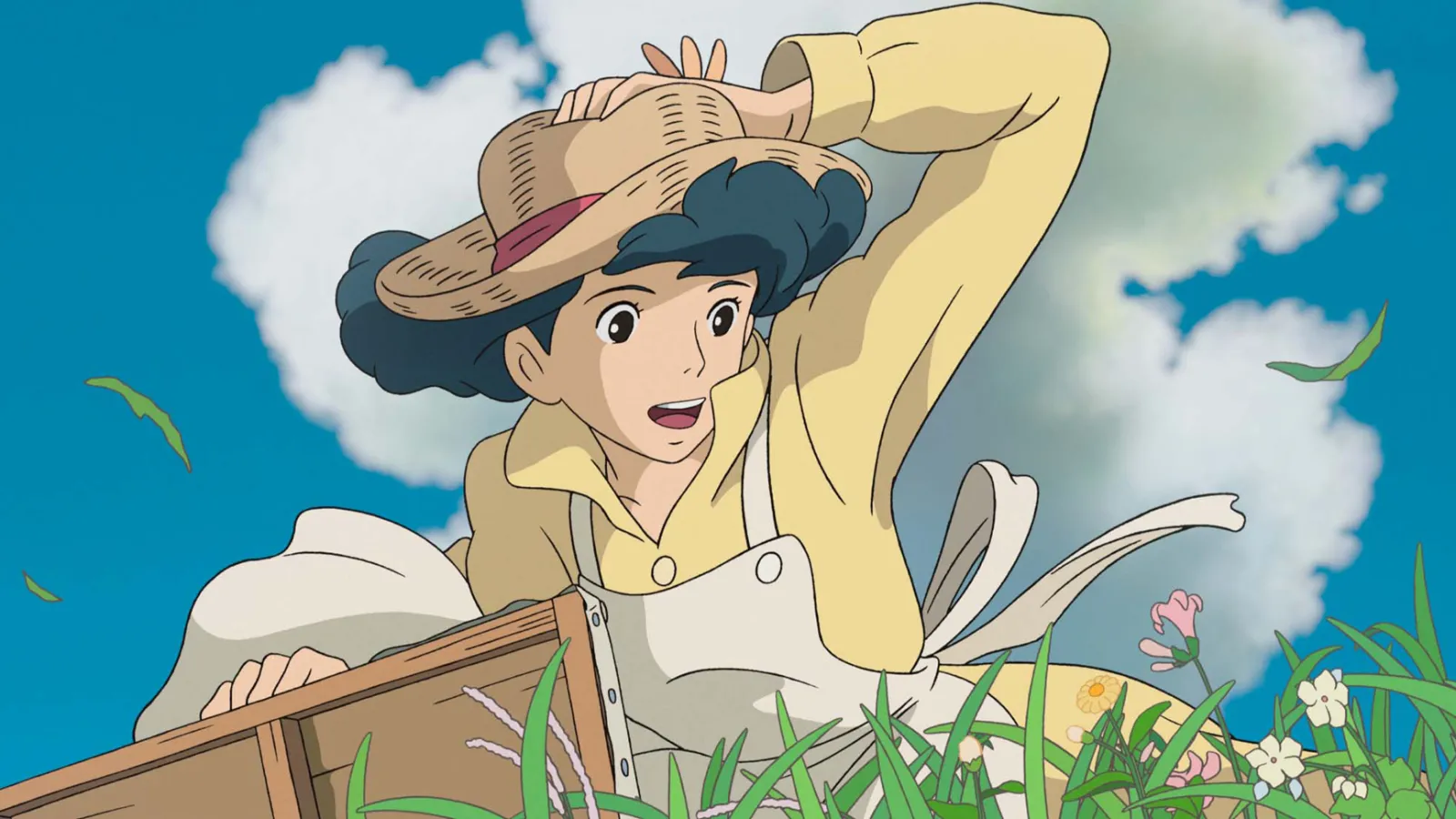

The realism of Ghibli’s painted backdrops once again shows face, allowing for a successfully grounded world for our characters to live in, unlike the more magical of Miyazaki’s works. While we observe the real world, colours are identical to how they seem in real life, meanwhile as our protagonist experiences states of euphoria, whether at the majesty of planes gliding through the wind in his dreams or at the love of his life, colours splash out at us in a whirlwind of radiance.

Despite being fictionalized (existing as a combination between the real-life accomplishments of Jiro Horikoshi and the 1937 novel, The Wind Has Risen) every character feels just as real as the world they live in. Characters who at first seem more like caricatures (namely, Mr. Kurokawa) are seen to be far more three-dimensional later on.

Like Yoshifumi Kondou’s Whisper of the Heart (1995), The Wind Rises tells a story of the search for perfection in art. Unlike in Whisper of the Heart however, in which the story is about how an young artist’s perfectly polished gem requires practice and can’t be found immediately, this film shows the journey to achieving that perfection, and how your perfect gem can be corrupted.

Miyazaki heavily leans into Jiro’s struggle with the eventual effects of his craft. With numerous warnings throughout the film, such as Jiro’s initial dream sequence or his conversations with Giovanni (granted, ones in which he encourages Jiro to pursue), Jiro still chooses to create his dream, advancing the war effort and supporting his country’s imperialism.

We’re not arms merchants, we just want to make good aircraft.

This quote delivered by Jiro’s friend and fellow airplane engineer shines a light on what the thesis statement of this film is; ‘these designers of war machines aren’t responsible for the way their war machines are used!’

But they knew how their machines would be used. Their dream was cursed, and they knew it. If you’re getting paid to create a weapon, that makes you an arms merchant.

One could argue this statement is simply the sentiment of Honjo, and perhaps other deluded engineers, and not Miyazaki himself. And I’d almost agree, had Jiro (or if the line was stated somewhere else, another character) made any counterpoint. The film makes no effort to condemn the engineers (or to provide a perspective in which they’re not at fault), despite their inherent responsibility. It actively chooses to distract from Jiro’s liability in favour of exploring his passion for the craft.

Actually, Miyazaki’s decision to distance this man’s passion from it’s context does come with it’s benefits, as it allows for another story to take hold; Jiro’s story of love and loss.

The Ghibli veteran exhibits his exceptional storytelling abilities by making way for a heartfelt, tender romance alongside the businesslike biography of a passionate inventor. By allowing the audience to spend valued time with Jiro and Naoko, he makes the heartbreak of her increased sickness, and later death, even more devastating and horrific. Having seen so many of the pure moments during their short-lived time together, we feel the loss just as much as Jiro does.

Miyazaki gives hope however; the final words his wife gives to him are a truth that the work-addicted Jiro likely wouldn’t have realized on his own;

You must live.

As his beloved fades away and her umbrella gets swept away in the breeze, Jiro chooses to take these words to heart. We can effortlessly imagine, as authentically as Jiro’s dreams of aircraft, him enjoying a warm tea on a balcony facing the forest; lying on the grass looking up to the stars; pastimes that only children, in all their genuine wonder, conventionally carry out. We can imagine Jiro deciding to truly live in the midst of a complicated, cruel, windswept world.