Literally, it actively refuses to be understated or relaxed, it will not slow down.

Miyazaki spiritedly creates his own live-action genre film in animation with Lupin the Third: The Castle of Cagliostro, a brilliant directorial debut from the animation auteur. The absolutely bonkers action never fails to excite from the historically meditative Miyazaki, and his inspiration from 1960s action capers takes the form of one of the man’s main philosophies; it goes beyond itself and improves upon those earlier crime thrillers.

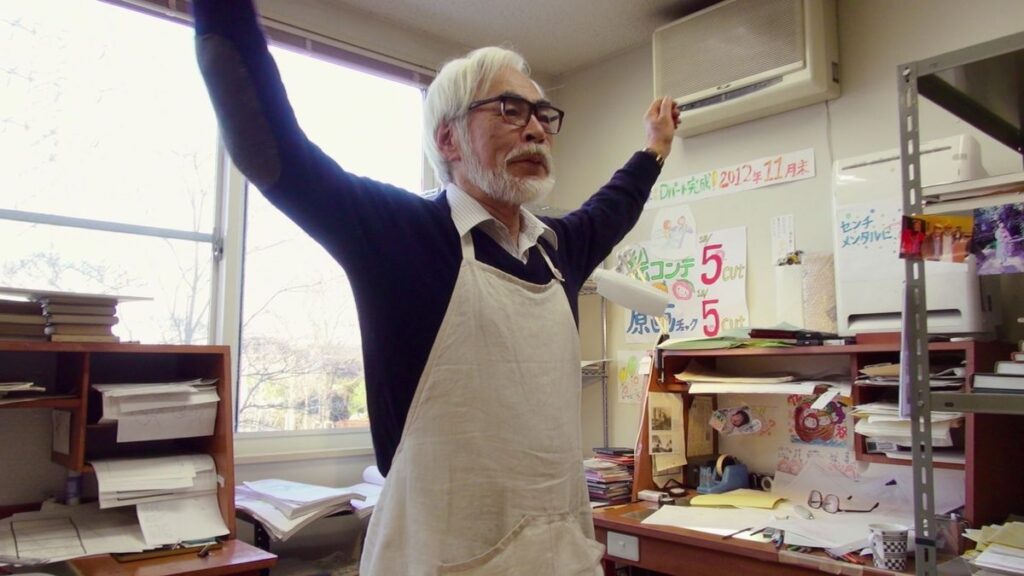

To deny Miyazaki’s impact on film and the world in general would be a futile effort; so many Pixar employees have cited his films as their inspiration (namely Enrico Casarosa, director of Luca) as have any number of Dreamworks employees, and other anime artists. But who would have known that even with Miyazaki’s first feature, he would influence the likes of John Lasseter, who became Miyazaki-obsessed after seeing a clip from Cagliostro, Ron Clements and John Musker, paying homage to the clock tower sequence at the end of their film, The Great Mouse Detective, and even Lupin’s own Takashi Yamazaki, who chose to replicate Cagliostro’s vivacious tone with his feature, Lupin III: The First.

It has also been speculated to have inspired George Lucas and Steven Spielberg for the Indiana Jones trilogy, considering their similar tones, however this has been contested due to documentation stating Raiders of the Lost Ark had a completed script in 1980, before Cagliostro ever got shown in the US. On top of that, the film never got a wide release until 1991, after the Indiana Jones trilogy had concluded in 1989 with Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, making this speculation hold little water.

Nonetheless, it is a testament to the film’s originality that it brought something of the same ilk as Indiana Jones before that film had been conceived. Miyazaki’s goals with the film were to drop the ruthlessness of the original Lupin character, and the grittiness of the Lupin manga, opting to create a more preposterous world for him to inhabit (similar to the campiness of the action serials that inspired Raiders). At the point the series was at, several interpretations of Lupin had already been created, so Miyazaki was comfortable reinventing the character’s personality and breaking away from Lupin’s poisonousness.

His new outlandish world, he thought, would eliminate audiences’ automatic reproach towards thieves, believing that as long as Lupin’s surroundings were equally as ridiculous as him, his likeability would be assured. His line of thinking was based in the idea that if Lupin were stealing from the ordinary people of the real world, ordinary people that the audience would relate to, they would find the character displeasing and repugnant (something that had not been a problem for the vicious Lupin manga, which served to further stigmatize criminality through the character’s remorselessness).

The impishness of both Lupin and his context excels as a tone, and the liveliness stems into the film’s action; a particular highlight overall. The screwball pursuit scenes are truly joyous, and the opening car chase solidifies precisely what to expect from the following 90 minutes. It’s nothing less than delightful to experience the animation’s vibrancy enliven the character movement, pushing animation to its (unlimited) limits and making for the purest of hand-drawn spectacle (additionally, keen-eyed viewers will find Chaplin homages during the clock tower sequences; how could one not be pleased watching this?).

The animation is surprisingly strong for a 1970’s film, equivalent to a lower budget animated film from the late 80’s. The main complaint to find would be choppy frames at certain points during fast-paced action sequences, but the individual drawings are already so distinctive, the movements stay discernible. At points, there’s also an unfortunate lack of shading when the story would call for it thematically, and the colours feel more artificial than they should. Castle in the Sky has around the same budget as this film, which should tell you the difference years can make when it comes to animation quality and timelessness.

Even so, these minor issues bear no scrutiny, as the complex character movement will do more than enough to evoke the intended emotions. Each frame of animation is used to tell the story, such as when Cagliostro first realizes that Lupin stole the ring from Clarisse. There is no line that references this, we see it all in his expression, and Miyazaki shows respect for his audience by allowing them to understand the scene through just visuals and context.

Cagliostro’s score works best at its jazziest, as it exhilarates with a breakneck swing rhythm and loud brassy booms. The personality of each exciting skirmish is given ear-pleasing flashy accompaniment, and it only amplifies the elation brought out from these scenes. When it attempts heartfelt emotionality, using a grand and contemplative orchestra to elicit such a reaction, it comes across as lamely sentimental, and it fails to reach the heights of the bouncy big band melodies.

Precursors to some of Miyazaki’s later visual decisions can be seen, such as the mistiness of the flooding water when the dam is broken, later used to great effect in Spirited Away‘s bathhouse. The bright, grassy landscapes of Kiki’s Delivery Service and Howl’s Moving Castle are very reminiscent of the ones seen early on in this film, likely because of the sketches Miyazaki made on a research trip for Heidi, Girl of the Alps that inspired scenery in many of his future films. We even see the beginnings of his trademark imaginary flying machines, likely the first expression of his obsession with aircraft in his art. While the film remains tonally different to his later Studio Ghibli features, Miyazaki’s personality and distinct creative touch fails to leave his work.

Lupin’s character writing is especially well-done, and Miyazaki’s interpretation of him is precisely what you’d want to see out of an espionage protagonist. The character isn’t an idealistic paragon of all things manhood should be, in fact, he’s almost the opposite of the like. Though he can accomplish impossible feats, his stunts are performed clumsily (despite his confidence) and afterwards he stays humble and bashful. This is directly contrary to the forced coolness of today’s action stars, where every surrounding non-character constantly compliments some aspect of them, and success is assured for each and every action they take.

At no point does the film force its coolness upon its stars: experiencing each one display their personality and bounce off one another’s chemistry gives you a sense for their familiarity with one another, as well as their genuine charm. Charisma is accomplished naturally with the stylish framing behind every shot, the music that personifies the characters’ spirit, and the suave straight-to-the-point dialogue. It actively demonstrates that to be purely ‘cool’ means not to desperately cling to perfection; you stay human and accomplish your goals without pride.

Well, I’m sure scared. I’m so scared, in fact, that I’m gonna catch some Z’s.

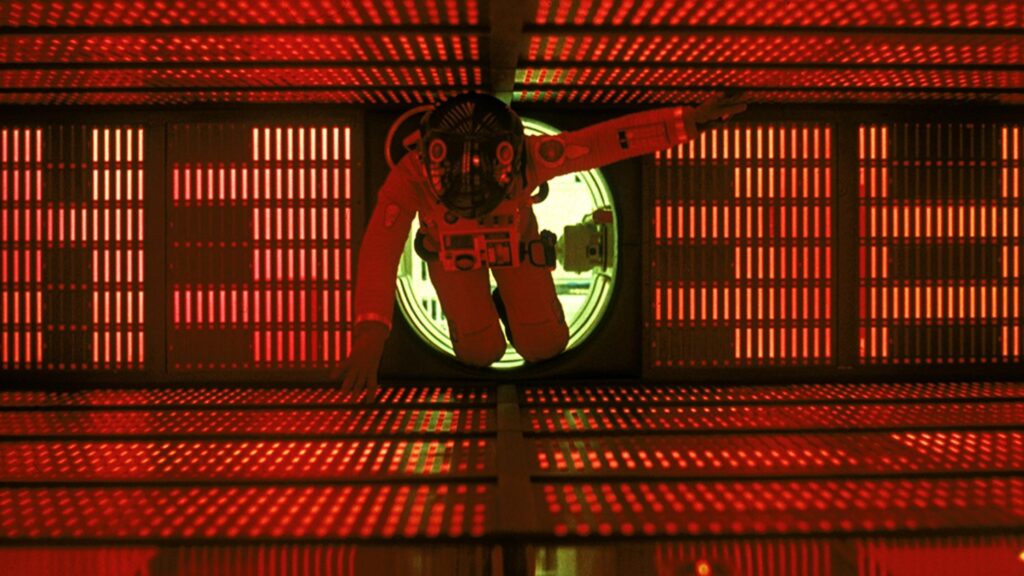

Unlike the Western action films of the era (and modern day), the film refuses to display a worship of government power, actively mocking it in the process. The rich are the villains, while the skilled thieves are heroes for stealing from them, as opposed to anyone equally disadvantaged. Interpol agents bear the brunt of slapstick ridicule, gloriously lampooning and undermining destructive intelligence agencies (a completely contradictory ideal to the imperialist propaganda that plagues otherwise well-made action movies), along with Cagliosto’s guards, a symbol of a more powerful political force. Still, none of these pawns are deemed responsible for the oppressive actions of such powers; only the ruling class fascists are given their comeuppance. The heroism represented by our characters is true class justice; Miyazaki highlights injustices brought upon by governments and the ruling class, before allowing our heroes to triumphantly knock those injustices down.

In the sewers of Cagliostro’s castle, thousands of bodies are stored. His empire is built off the foundations of others’ backs, his capitalist success only possible with the oppressed dying below him. This suffering is assured for anyone to have such political influence and make such ridiculous profit. Zenigata, realizing his superiors at Interpol won’t prosecute Cagliostro out of fear of political repercussions, chooses not to give up and accept that the political figure won’t be found culpable, he devises a plan to expose his fraud. When faced with the threat of Cagliostro taking complete ownership over ancestrally preserved treasure, Lupin’s rogue vigilantism is what ends up ending his reign. Miyazaki’s heroes are progressive and actively take stands for the change of the most deeply-seated of political and economic concerns, rather than reinforcing the ideals that preserve capitalist status quo.

Miyazaki’s first seat in the director’s chair creates one of the most inspiring works you can find in genre filmmaking, and though you can tell he was a little more comfortable sitting in on later films, Cagliostro stands on its own as an espionage caper. The pure excitement that brims from this movie should be enough to inspire you to check out more of Miyazaki’s filmography; then again, most people probably watch this because they’ve already exhausted watching everything else in there. Even so, my point is that it’s more than just a fine film, it’s one of the most substantive and delightful experiences you can watch on a screen.

Put simply, pure artistic brilliance.