Kevin Williamson’s screenplay uses your familiarity with the horror genre against you, with help from Wes Craven’s master craftmanship.

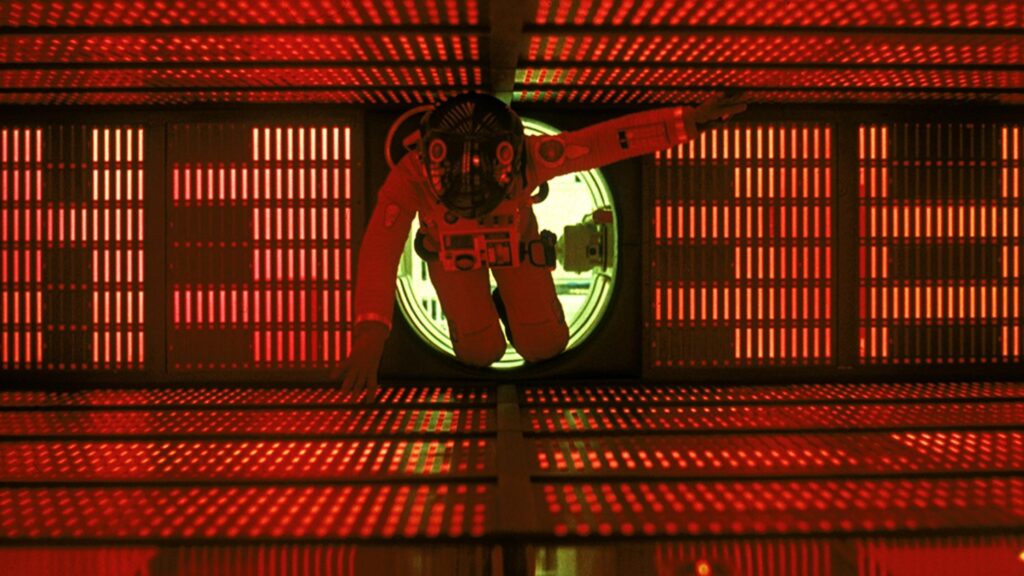

In 1984, the Wes Craven-directed A Nightmare on Elm Street was released to immediate acclaim. Like Halloween and Friday the 13th before it, the movie proved itself worthy of a legacy far exceeding anyone’s expectations, as its wild and surrealistic take on a conventional slasher plotline cemented its status among the era’s classics. After two decades of mainstream audiences’ gradual familiarization with even the most creative of these genre subversions, it was determined by emergent screenwriter Kevin Williamson that horror movies needed an immediate adrenaline shot; a satire of slashers which could actually elicit fear among modern moviegoers by preying on their savviness to the genre, to the “rules” of horror filmmaking.

Williamson’s premise is well-suited to his aims, decorating a small California town with irreverent teenagers who are hyperaware of the tricks, conveniences, and moral impositions of the very type of movie they’re starring in. Whether they consume a constant diet of B horror or casually watch the occasional Jamie Lee Curtis feature, their perfect comprehension of these films’ structure is matched only by the unseriousness with which they treat their identical situation, a mistake which (spoilers!) the slain Casey Becker, Principal Himbry, Tatum Riley, and more pay for at the hands of Ghostace’s dual personae: the visibly psychotic Billy Loomis and Stu Macher.

When Billy sneaks into his girlfriend Sidney Prescott’s window shortly after the opening kill, or when Stu admits that not only is Casey his ex-girlfriend, but she broke up with him in favour of the also murdered Steve Orth, our suspicions are raised — but never exactly confirmed. Throughout the runtime, these two make it extremely obvious that they are unstable, maniacal, unempathetic, and in Billy’s case, unhealthily obsessed with referencing old horror movies. They would come across like burnouts in any real high school (with a little tryhard mixed in), but here, every aspect of their behaviour is a giant signpost for serial mania. It is a testament to the strength of the screenplay that their guilt is so retrospectively obvious, but through little more than a stream of red herrings and the audience’s assumption that they’re being misled, we allow our speculation to run wild.

Essential to Scream‘s appeal is its subversion of our intuition of what a movie like this actually is, where it’s going, and who it’s going to sacrifice; it’s a whodunit where that very question — who is Ghostface? — is a joke. Most of us know that it must be Billy the whole time we’re watching, and it’s only Stu’s appearance as a surprise accomplice that leads us off the trail. In a vacuum (without glancing at any of the sequels’ posters), we expect Gale Weathers to be one of Ghostface’s victims given her sheer lack of likeability as a tabloid opportunist, yet instead she redeems herself by nearly getting the best of the two killers. At the end of the movie’s lunatic finale, it openly mocks the idea that Billy would spring back into life for one last scare, a cliché that had become excessive in the explosive, never-ending climaxes of blockbuster thrillers like Cape Fear. The subjects of Scream‘s satire are far-reaching; part of its openly broad-strokes approach to disorient anyone who believes they can accurately predict exactly which tropes it will drop, follow through on, or outright mock.

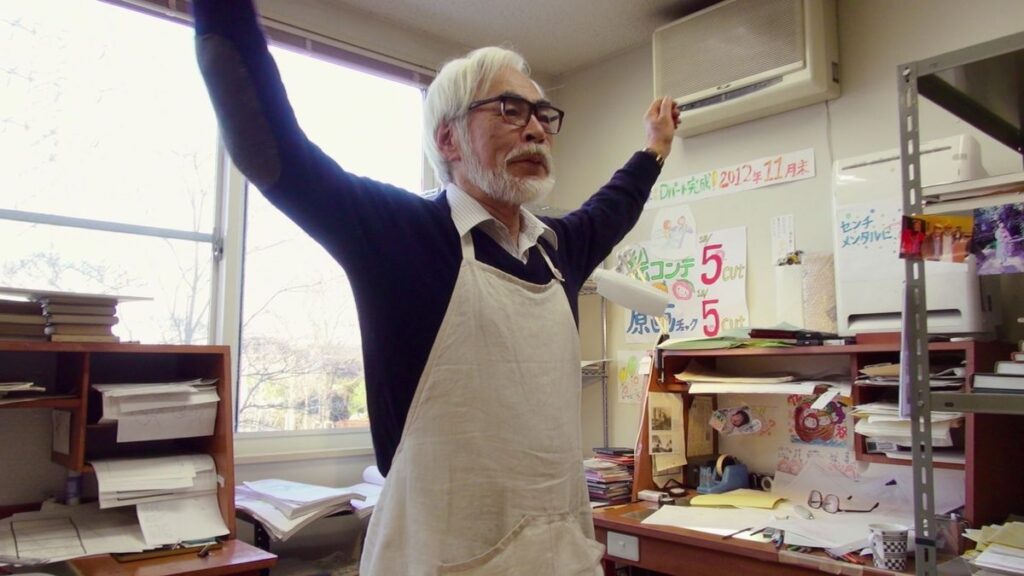

Much of Scream‘s achievements are the achievements of Wes Craven himself, a man who had been so responsible for the reputation of the horror genre at large when he was commissioned to helm this reimagined take, and who understood that even in a satire, the prominent humanity of the characters is essential. In Nightmare, it was the strained relationship between a daughter and her mother, and here in Scream, it is Sidney’s residual trauma for her mother’s murder — a widely publicized event which has ruined her adolescence. She is devastated by the sensationalization of the murders which surround her while starring in a movie about sensationalizing murder. Even Billy is not just a ‘creative psycho’, but an unstable personality who felt so slighted by the abandonment of his mother that it inspires a killing spree. The dynamics of these well-drawn characters set the stage for every set piece, lending them a weight that parody could never provide.

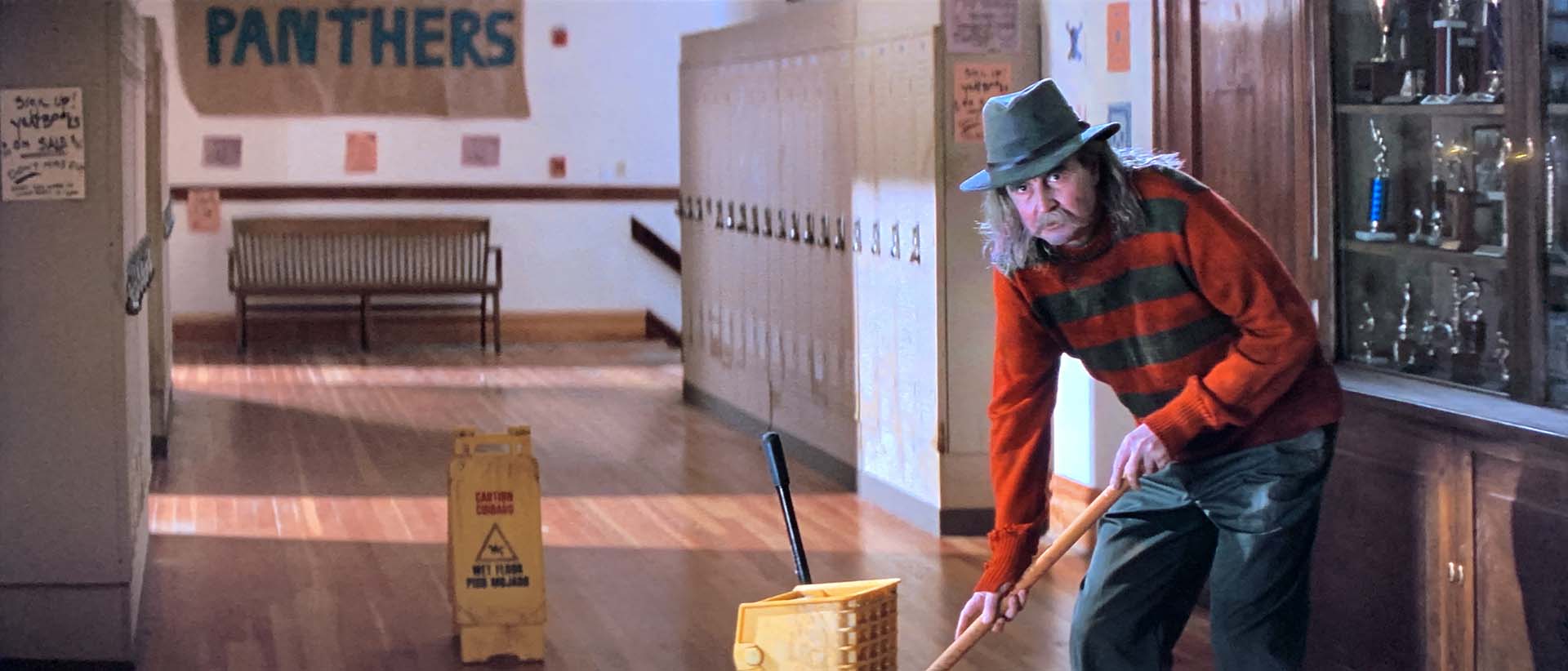

It is a testament to the sheer, unadorned passion from which Scream was created that it can be so infused with snark while never minimizing this genre’s legacy — there is an explicit adoration for this style of film which elevates the bigger picture, visibly influencing the spirit of the whole filmmaking process. Craven obviously harboured some bitterness towards anyone who prohibited that process; after a handshake deal had already been secured with a local school board to grant filming permission in one of the city’s high schools, permission was suddenly revoked days before principal photography began after objections were raised to the movie’s requisite violence (most offensively, the fact that the script called for the brutal death of a faculty member). This disruption allegedly cost the already tightly budgeted production hundreds of thousands of dollars. Today, if you watch Scream to the very end of the credits, you’ll see the message: “No thanks whatsoever to the Santa Rosa City School District Governing Board.” An appropriately frustrated final note from a movie so zealous about its artistry.