Human industry’s willful exploitation of nature is met with violent revenge from the forest’s protectors in Miyazaki’s deeply political epic.

Anyone who knows Miyazaki knows one of his hallmarks is his child-friendly whimsy. While his films can certainly be enjoyed by people of all ages, as any good children’s story can, they are still targeted specifically to appeal to children. It’s comforting, the philosophy of his films. He understands the outlook of a child is the most optimistic outlook in the world, and he chooses to instill these values of love and happiness among children.

Princess Mononoke, while darker, is no different. Children are given a beautiful message of love, and adults can recognize the incorporation of themes of environmentalism that are based in reality, specifically criticizing destructive economic development.

It uses animation to render one of the most uniquely creative worlds ever put to film, and uses that world to reflect problems in our political reality. The story is told with humanism and complex character writing; moral simplifications are cast to the wayside and the conflicts of the film are profoundly weighted and deep. Nothing is black-and-white, just the same as the real world his narrative reflects.

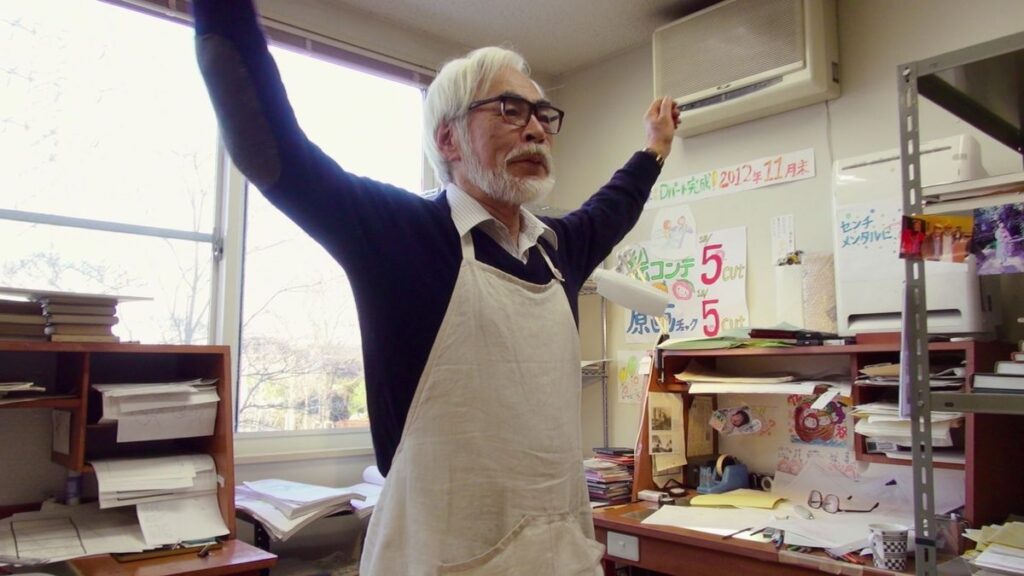

The concept of portraying evil and then destroying it—I know this is considered mainstream, but I think it is rotten. This idea that whenever something evil happens someone particular can be blamed and punished for it, in life and in politics is hopeless.

— Hayao Miyazaki

Miyazaki’s philosophies are thoughtfully explored here, and his sincere connection with both humanity and the natural world is evident. He has a genuine love for both these often conflicting worlds, and wants more than anything for them to co-exist; he understands they can, and calls for this kind of change in each of his narratives. A nuanced look at environmentalism devoid of any sense of ecofascism or defeatism.

The world created by Miyazaki and the Ghibli animation team encapsulates everything great that can come about with an imaginative vision. They show us an expansive fantasy world of enormous talking wolves, a glorious red elk, an army of imposing, raging boars, a demonic curse that consumes the violent, and an abstract, vividly beautiful yet haunting forest spirit, while simultaneously keeping their story grounded and personal, effortlessly weaving its way between these two tones, along a cohesive narrative thread. Miyazaki’s unique approach to storytelling is clearly present here, and the film’s narrative identity matches Miyazaki’s other work; it’s jarring to watch an intricately plotted epic that coasts its way along, slowly washing away until a sudden end.

If you’ve seen any Ghibli work whatsoever (save perhaps Ocean Waves or The Cat Returns; great animation, just not masterful) you don’t need a reminder on their unmatched proficiency in animation. The linework here is impeccable, and commencing the current era of Ghibli in which they use digital resources to animate their films (in this case, digitizing the hand drawn artwork for a chiquer look, as well as intermittently using computer-generated 3D images for objects like the grotesque demon snakes), it’s clear they immediately knew how to adapt their newfound software assistance to their classic hand drawn style economically. It’s not a movie you’d criticize for having ‘dated effects’ and I wouldn’t be surprised if a significant portion of viewers failed to notice there was any 3D animation at all.

Our unspoken characters are among the most joy-prompting from Studio Ghibli, such as the whimsical Kodamas, or the majestic red elk, Yakul, who stands in proud loyalty to Ashitaka. Miyazaki goes the extra mile to give these non-essential, story-adjacent creatures characterization, making his world feel all the more lived in.

Miyazaki’s proposal for the film described a subversion of the preconceived expectations of Japanese period dramas of the time. He wanted his tale to be one that depicts a freer Japan than conventionally seen, one in which the forests were dense, and people were more scarce. He wished to show the more sparsely seen settings of ancient Japan, and characters that rarely took the main stage. He wished to demonstrate the fluidity of structure at that time, when social upheaval had been regular.

Instead of conforming to the rigid structure of period dramas, he chose to create a more chaotic art, and tell a story where poverty isn’t tolerated, and the contours of society were not clearly defined.

Interestingly, the production of the film saw Miyazaki, Masashi Ando (Mononoke’s supervising animator), and a variety of members of the art/animation team travelling to the ancient forests of Yakushima to find inspiration for the look of the Cedar Forest. It had also been an inspiration for the aesthetic of the forests in Miyazaki’s Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, which certainly shows, given the similar colour scheme and atmosphere of both.

The forest of this world is expansive, but under the very real and imminent threat of utter annihilation. When the evil of the human industry manifests itself in the boar god Nago’s bullet wound, the prince of Emishi village, Ashitaka, is forced to kill the animal in defense of the people. The curse that had taken over Nago infects Ashitaka in turn, his violence now disciplined, the pain inflicted by other humans now unjustly affecting him. He must now be banished from his village, in search of a cure for his curse.

Early on in his journey, he discovers samurai attacking villagers. When he instantly shoots off the arms of a samurai on impact, followed by the decapitation of another, it’s at first assumed that this is Miyazaki gleefully revelling in cartoonish ultra-violence after years of a more child-friendly affair, while we later realize this is a symptom of the demon he’s infected with; this is not intended to be joyful escapism, but Miyazaki showing his disdain for violence yet again in his art.

The moment townspeople realize Ashitaka has gold, they make an attempt to steal it. By way of the systems in place, ordinary villagers are forced to turn against one another instead of uniting and uprising against the system that keeps them in a life of poverty.

We see Ashitaka travel back and forth between worlds; including that of Lady Eboshi: a despicable leader who exploits the resources of nature for her iron industry, steadily annihilating the homes of the animals, reducing their numbers until near-extinction. She communes with the townspeople and gives off a friendly appearance; a strategy not unlike real-life modern day politicians.

But again, the morals are not so simple. Eboshi provides opportunity for all people; she allows the women to work in factories, and the lepers to produce Ishibiya guns for her. Every citizen of Irontown was once a member of a more oppressive environment, and she provides a comfortable sanctuary in her society.

The film paints the denizens of Irontown naively. Blindly, they follow, support and remain employed by an industry that exploits and destroys nature, just the same as the workers of the real world. And as for those career opportunities, the labourers have intensely high shifts, but accept this suffering because of their patriotism and inability to admit the fault of the community that they’ve attached their identity to; they are the citizens of every nation in the world. Miyazaki includes them to represent the dangers of nationalism. They accept a poor situation just because ‘it’s better than it was.’

Still, these ironworkers are not completely fargone. When the commander of the abled-bodied male townsfolk makes an attempt to kill Ashitaka, they revolt against him, denying the instructions of their leader to help their people.

Instead of painting a standard picture of good and evil, Miyazaki allows for different interpretations to be applied; a wild and complicated tableau of several ideas interlocking with one another. Easy solutions are not provided, nor are oversimplified problems.

Ashitaka associates with the animals along his way, discovering the culture of the wolf clan. Led by Moro, their goal is to unite the animals of the forest again; and reinstate their loyalty to the Forest Spirit. The animals’ collective crisis facilitates division among their clans, and it’s difficult to reason with them to come together and form alliances in all their rage. All of them are having their homes obliterated, and none of them can come to a consensus on how to end the destruction.

The boars are one of these clans; they are also condemnations of national pride. Only they are far more simple-minded, tempered, and quick to seek out forceful solutions to their problems. They are the radicals of political struggle; they’re on the right side of the issue (experiencing and attempting to end suffering) but the way in which they go about it isn’t very helpful towards their cause at all. By being so violent about their cause, no one’s opinion is overturned on the other side. They too are blindly trusting of their leaders and believe every one of their claims, no less naive than the ironworkers. While Moro’s clan is similar, they realize a violent fight is not the way by the end, nor are they nearly as radical in the first place.

The boars are a proud race. The last one alive will be charging blindly forward.

And violence: Miyazaki hates it. We all know he hates war, that’s seen in all of his work. Even here, a troubled soldier recounts his war story in which the nation who sent him out cares not for their very own troops; only victory. Deliberately, they employ military tactics that waste the lives of their army. A metaphor for oppressive nations selfishly throwing large portions of their population’s lives away, all to sort out the oppressors’ own issues, rather than the issues of the people.

But violence? It hasn’t really been explored. Yes, Miyazaki has indulged in a cartoonish, energetic violence on people during his action sequences, and similarly cartoonish outright destruction on man-made objects. And obviously, violence is inherent with war. And sure, politically, violence is often just another word for a group attacking another.

But here, real-life violence specifically is condemned entirely. Any act of violence. It’s not right. Miyazaki displays the philosophy that hate is learnt, and love is the natural behaviour of human beings (as well as humanized animals). As such, violence is barbaric, no matter the context. It cannot be just, even if it leads to a righteous cause; it makes you just as corrupt as the oppressive force.

Miyazaki argues that violence does not need to be responded with more violence, a sentiment militaries around the world would not echo. The boars fail to grasp this, Eboshi engages in violence while understanding her own malevolence, Moro simply doesn’t agree with this philosophy, and even San can’t learn it until the end.

Only the righteous protagonist believes in this throughout our story, for the animals, that retaliating against humans will only create more hatred. Yet not even he can stay completely guiltless; long after realizing instant kills from his weapons are a symptom of his curse, he chooses to decapitate a few more samurai. Miyazaki, while condemning violence, simultaneously understands that it’s an inevitability of social struggle. A paradox.

And still, Miyazaki’s creativity shines through in his physical representation of the inherent inhumanity found in violence. His demonic snakes symbolize rage and hatred in a grotesquely horrifying way, appropriately vilifying the brutality by representing it as a horrible curse.

The ending provides a strong message on environmentalism and one of the main themes of the film; that nature will destroy you, if you destroy it. See, Miyazaki made an attempt to deny his past works, in which he often portrayed nature as passive and benevolent, and make a film where nature strikes back against human industry, similar to Takahata’s Pom Poko. This is conveyed in the film through nature’s savagery, as well as the forest god directly annihilating the symbol of nature exploitation, Irontown.

At the same time, the film’s conclusion in Irontown could be interpreted as idealism; the oppressive leader admits their fault and changes her society’s industrial ways. In this conclusion, economic reform is not brought about with a fight from the collective; in fact, the collective doesn’t even seem to be interested in maintaining environmental balance. Her previous psychopathic behaviour is ended simply by viewing the destruction she creates. It’s unrealistic, but I see it as more like pessimistic irony on Miyazaki’s part; a sighed admission that corrupt leaders would never end their heartless acts of their own volition. He gives a sardonic glimpse into a fictional occurence where one does.

We’re going to start all over again. This time we’ll build a better town.

Still, she learns a lesson. A leader stops her oppressive, destructive ways. She decides to replace her existing destructive industry methods, to coexist with nature. That’s what it means to save it. If only. Why does this have to be an impossibility!?

[After Toshio Uratani mentions to him that his film may be dealing with too many complex problems at once]

It’s an unsolvable problem, isn’t it? In the past, movies presented small problems that could easily be solved.

— Hayao Miyazaki

In 2003, when Spirited Away was nominated for Best Animated Feature, Miyazaki refused to attend the ceremony in protest of the invasion of Iraq, and the Oscars’ involvement in distracting from it. He took a stand against the despicable behaviour of the country he was receiving an award from by undermining its power. That’s something not even Michael Moore could do, who while receiving his award for Bowling for Columbine, merely spouted out (accurate but) unnuanced, unhelpful liberal finger-pointing statements; statements whose only worth was in reinforcing the opinions of those who were already against the Bush Administration.

They’re statements I agree with, and Moore is a documentary filmmaker I like, but the political opinions expressed in his speech display little more than a narrow-minded hatred on the surface; Miyazaki’s protest resonates more profoundly.

In 2004, he made Howl’s Moving Castle, a direct allegory for the Iraq War, in which he employs his unique storytelling abilities to deliver themes of prejudice, propaganda, and destruction. His contempt for war, and his assertion of government’s fictionalized justifications for it, is expressed diplomatically and brilliantly in this, as well as the rest of the more political films in his filmography.

In his films, he teaches not hatred, but love. He teaches the children who watch to embrace love and restrict the hate and depravity around them.

That’s why this ending doesn’t have to be impossible. Though Miyazaki is most definitely pessimistic in his real-life, that doesn’t stop him from including optimistic and idealist messaging in his work, providing inspiration in a world that is so often disheartening.

As politics stand, they’re an unsolvable problem. Purposefully complex and confusing, the systems of oppression remain rigid and unmoveable. But Miyazaki provides a chance for the future generations. For them to overcome the evilest of authorities, to preserve others’ innocence, and maintain a balance of nature and human existence. Not to be physically violent, not to blindly charge onto a battlefield for no reason, not to think of the world simple-mindedly, not be wrought with hatred. But to focus on living. To allow for humans and nature alike to live equally and equitably.

A society cannot be perfectly just (where good comes so does evil) but it can be better.

We can be building a better world.

It’s not hope, but a call to action.

Live.

You must see with eyes unclouded by hate. See the good in that which is evil, and the evil in that which is good. Pledge yourself to neither side, but vow instead to preserve the balance that exists between the two.

— Hayao Miyazaki