Satoshi Kon uses his powers of composition to confront his audience with the horrors of an industry that destroys women’s lives.

When brought into the realm of animation, stories are given infinite potential to go beyond themselves and exceed the barriers of live-action narratives. Within an animated setting, architecture can interlock with the subjects inside it, sculpture can manifest as a character, painting can flow as a whirlwind of colour, literature can have life breathed into it, music can overlay emotion onto a greater canvas, and performance can be accentuated with intimate linework. Every achievement in animation is more impressive than those in live-action because in animation you are creating, not simply recording.

That’s why the thought that Perfect Blue could tell its story just fine without animation is inherently flawed; every story could be told better with animation, and Perfect Blue embraces that sentiment more tightly than any thriller I’ve ever seen. How horrific would the murder in front of the projector be had the colourization not been hand-done? How haunting would Mima’s apparition be had her balletic floating been accomplished with green screen? Satoshi Kon knows these moments would work in live-action, but being an animator, he chooses to transcend this story’s limits through animation.

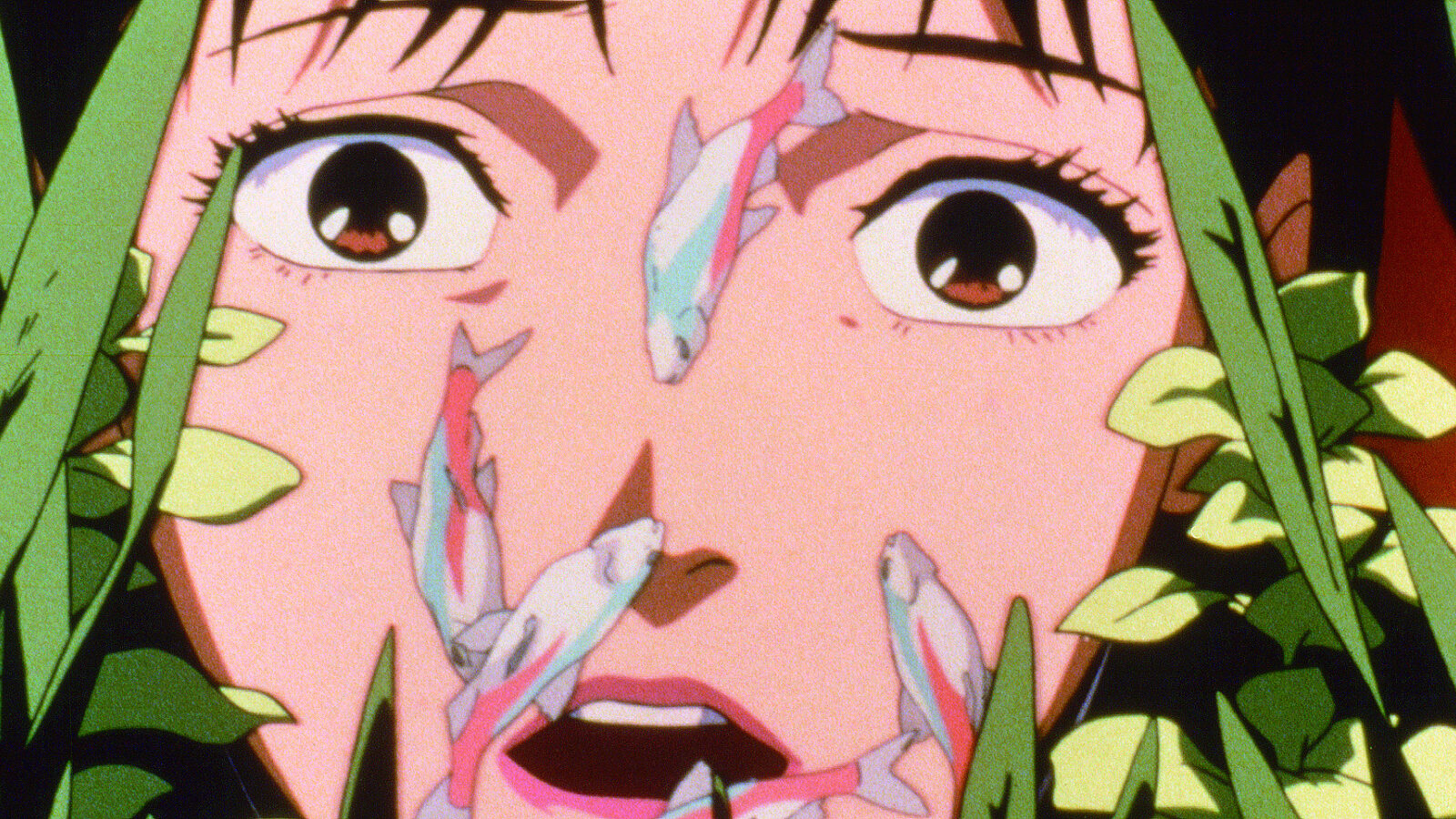

Kon trains his audience to expect a semi-standard character piece about a performer transitioning into working in a more sordid line of entertainment, before gradually heightening the intensities of the surreal imagery, trapping the viewer into the same accelerating chaos as its protagonist. Though we see glimpses of these nightmares early on, the horror truly begins commanding the screen during the off-putting discovery of Mima’s Room’s online diary, where Kon fixates on our main character’s horrified realization for much longer than needed to make his audience sufficiently uncomfortable.

Sufficiency is inadequate for Kon; he sets out to create art that excels.

Interpreting the film’s commentary further, it’s clear that Mamoru is not her only oppressor; patriarchy as a whole (from patriarchal violence to exploitation) is what causes her pain. Themes of surveillance pervade with crowds, cameras, and the ever-watchful urban setting; all of them depict the perceptions of entire portions of society, and their expectations of what career path she should follow. As these external perceptions blur her own, Mima becomes obsessed with the patriarchally angelic version of herself while she slays the patriarchally-formulated lascivious version of herself. Both are expectant for her to serve in a certain way, and both constrain her individuality; reducing her personality to mere photographs. The existing hierarchical structures of show business ensure that she cannot truly be comfortable with herself while performing; societal mindsets and the male gaze confine that.

Her dreamlike second persona while experiencing this image-based misogyny is where we find fantasy horror entering psychological horror, in the form of her (and Mamoru’s) pop idol apparition. She is the diary’s influence prevailing over her mind; the expectations of Mamoru (as well as other CHAM! fanatics) tormenting her and deluding her from her sense of self. Her entry into a more degrading image does this just as much, but the first-person perspective of the diary creates the alternate persona we see.

Of course, by its imprecise nature, the film eludes a comprehensive analysis, but it would be misguided to try and understand the precise mechanics of the story so long as you are able to interpret theme. Whether Mima was running from herself or Rumi in the climax doesn’t matter, as long as it’s understood that Rumi was one of the greatest opposers to the metamorphosis of Mima’s public image, and is therefore represented as such by violently strengthening her false sense of self. Whether Mamoru or Rumi created Mima’s Room doesn’t matter, as long as we know that both were outspokenly insistent on her pop idol appearance. Kon wants us not to understand his story on an absolute level, but instead understand its message on an allegorical level.

It’s Kon’s ability to effortlessly weave his way between dream and reality that allows Perfect Blue to stand out from other horror films. At the time the film was created, psychological horror was not a prominent genre in Japanese animation, and so there was no precedent that Kon could look to for guidance. By being limited in what he could take influence from, it seems as though his creative energy was allowed to fully spark, ensuring the visuals and tone of the film would be wholly unique in comparison to another anime works. While some visual motifs bear similarity to the suspense thrillers of Alfred Hitchcock, Kon makes them entirely his own here, giving them new life that would be impossible without true directorial talent.

That’s not to say that Kon deserves all the credit for the grunt work of his directorial debut. Composer Masahiro Ikumi (who has seemingly only ever worked on one other project besides this) creates a masterfully executed score that knows exactly when it should be held-back and when it should be heart-palpitating. Dialogue allows itself to resonate in the midst of echoing silence, but for the most disturbing or supernatural sequences, haunting breaths and metal clangs overwhelm the senses, entrancing the viewer into the same psychosis that has overcome our main character. These recurrent tones become synonymous with the most memorably eerie moments of the film and are a distinct aspect of the unforgettable experience the film becomes.

Another unforgettable aspect is the attention paid to effective colourization; under Kon’s oversight, colours are weaponized to procure the abject terror underlying every scene. Blazing red splatters of blood kindle a ringing madness during episodes of murder, before being abruptly contrasted with innocence (or vulgarity) in glowing white. The artificially bubbly atmosphere of musical show business is highlighted with bubblegum pink, until an imperfect blue exposes the realities of depravity. Every visual decision is essential to the film’s identity as a piece of art, and none of it would be nearly as exhilarating had it not been accomplished with animation.

Had this story not been animated, we would miss the ghostly beauty of curtains flapping in the wind to reveal a brightly lit room, because instead of every frame being hand-drawn, and the distinct shade of yellow hand-painted, they would simply be ordinary curtains plucked from a storage room, manipulated with a wind machine. Of course, there’s still artistry in creating such an effect, but by animating it rather than filming it, you add another layer of effort and of stylization. Animating requires building the physics of a world from the ground up, rather than maneuvering through real-life physics to conjure the desired artistic effect. In animation, the artist is in full control, while in live-action, they are restricted to the bounds of their world.

One of Orson Welles’s most memorable quotes is something he said to fellow filmmaker Henry Jaglom at lunch; “The enemy of art is the absence of limitations.” I agree with this quote in part; of course, a lack of resources requires you to think creatively and invent new methods of completing a task, while wielding total control and having full access to resources inevitably facilitates a mentality of finding lazy solutions to problems. However, because animation is entirely different from live-action film, it has its own hurdles that require creative thinking, bringing it into an entirely different creative realm. Though it’s ultimately a free sandbox, the difficulties of effectively making something out of that sandbox ensure it isn’t simply the artistically bankrupt landscape one might think. Personally, I think Kon’s surreal psychological thriller would suffer enormously without this beautiful art form, and quite possibly, every live-action film currently does.