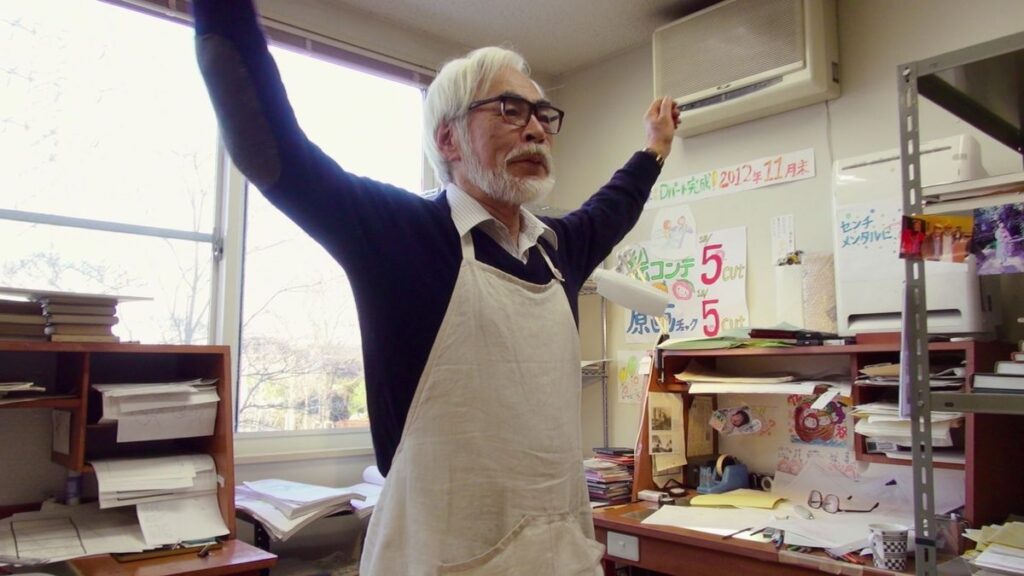

Noah Baumbach interrogates the cost of celebrity before turning around to congratulate George Clooney for his body of work.

That conclusive montage of Jay Kelly’s fictional film career consisting entirely of clips from George Clooney’s real film career sort of shocked me; it’s probably the strongest piece of evidence in favour of this being a vanity project. Somehow, after spending two and a half hours with this man and the actor portraying him (and noting the comparison begged by their alliterative names), I didn’t think the film would go so far as to make them correspond almost 1:1.

I can’t deny that I share Noah Baumbach’s and Emily Mortimer’s fascination with stardom, and I certainly do not mind George Clooney’s positioning as a millionaire movie star at the top of his game — especially given the fact that the movie Kelly has just finished filming at the very beginning bears a certain resemblance to a lot of Clooney’s recent, less blockbuster output. However, for these writers, that fascination begins and ends at reverence for the work tied up with grief for its inevitable, alienating effect on personal relationships. It’s nothing more than a sad cause and effect, something which Jay Kelly certainly draws effectively (using impeccable dialogue to do it), but no critique exists outside of that center.

We witness Kelly’s discomfort as the Italian superfans organizing his tribute event react to the headlines of his “heroic” takedown of a mentally ill handbag thief, but the tragedy seems to be more focused on how they ‘don’t see the real him’ than on how the media is oriented toward crafting entertaining, flattering narratives about celebrity figures. His legal team even attempts to cheer him up by celebrating about how they totally and completely crushed the lawsuit he was facing over his fistfight with Billy Crudup. Kelly feels bad about getting away with these things, but ultimately, we’re rooting for him to. We do not want to see him face a $100-million lawsuit; we’re sympathetic to his at once crass and dutifully careful maintenance of his own persona because he possesses the effortless charisma of George Clooney. So long as he and the script continue to paint Kelly as a ‘good guy’ while at once showing the increasing, presumably habitual lows to which he and his staff go to keep him stably at the top, there is a dichotomy which cannot be reconciled.

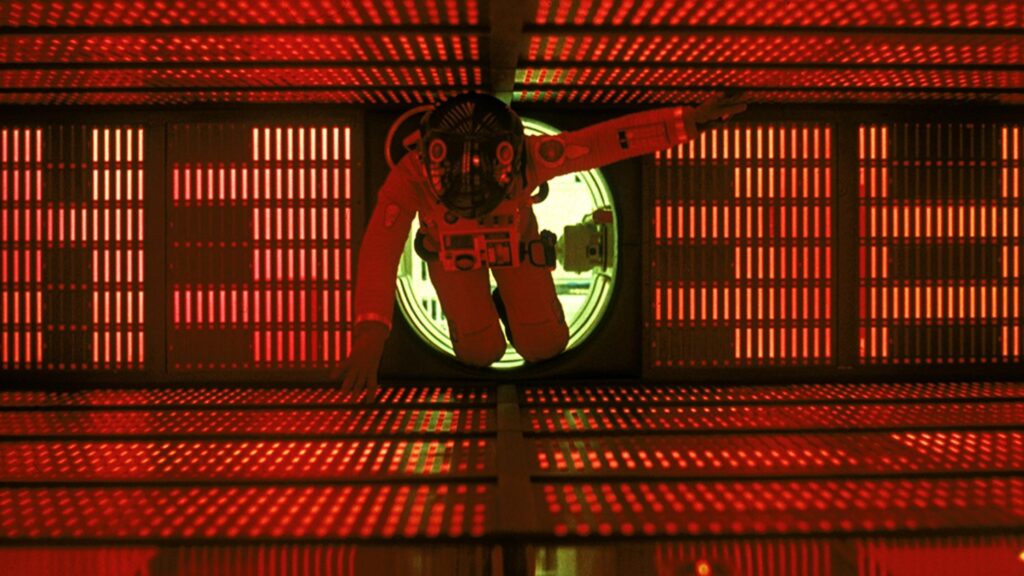

There is no doubt in my mind that Baumbach is pulling from Merrily We Roll Along at least slightly — perhaps he was more inspired by a richer history of cinema that I have not yet experienced and on which I have no commentary, but all the same, the themes of failing old friends while chasing the good life in Jay Kelly are distinctly reminiscent of those in Sondheim’s musical. If Baumbach makes any false move in treading the same territory, it’s in praising the importance of the work too much. Of course, George Clooney movies are great (Burn After Reading, two clips of which are featured almost back-to-back at the end of Jay Kelly, is elevated considerably by his performance as a pathetic narcissist), Noah Baumbach movies are great, Stephen Sondheim musicals are great — but if you are that artist, are you going to justify your murder of all other aspects of your life with the power of your art?

This is the content of the attempted critique of fame mounted by Jay Kelly and the Clooney clip show at its end, from which Kelly loses focus to imagine the expressions of all those who have struggled for his sake looking up in awe at his performances. They tell us that the regret over being unable to raise your kids properly, the futility of withstanding the demands of any relationship that is not heavily transactional, the heartbreak you create in others when you are not seriously engaged in being a friend to them are all worth it. Because not only were the movies you made on the way up great, you are great for having made them.