You have no reason to see this ugly and deeply uncomfortable mistake of a film.

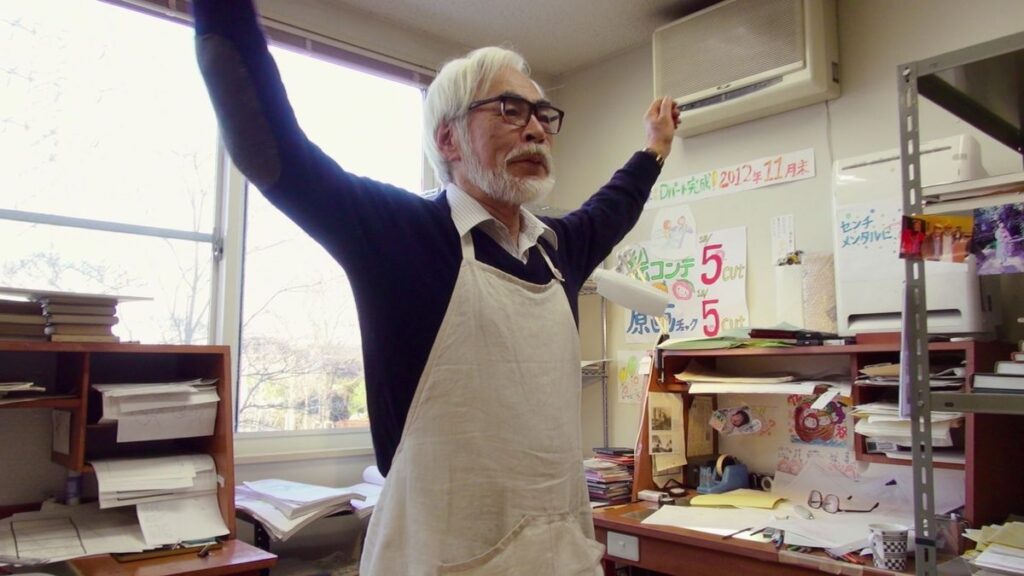

As I gazed upon the lifeless, manufactured movements of the great Studio Ghibli’s digital eyesore, the only emotion I could muster was sadness. Not sadness because their 2D era was over (their next film on the docket is hand-drawn and I expect their future works to follow suit), nor because some kind of imaginary ‘Golden Age of Ghibli’ was over (that next film is being directed by Hayao Miyazaki; we can expect quality). No, my sadness was aimed only at the film’s director, one Gorō Miyazaki.

Gorō is a deeply tragic figure, with a history of discouragement at every turn from his father, the Studio Ghibli where he works, and the critical world. The man studied landscape architecture all his life with the support of his father, content that he would never reach the artistic heights of the lauded auteur (at the very least, not ones in his father’s field). His first association with Ghibli outside of bloodline was when he planned out the Ghibli Museum in 1998, and later served as director when it opened in 2001, a feat that impressed Ghibli’s third master, producer Toshio Suzuki. It was Suzuki who pushed Gorō to make the shift from architect to director in 2005, a shift that surprised everyone with its abruptness, including Miyazaki.

When the decision was made to attach Gorō to Ghibli’s Tales from Earthsea project, Hayao, a long-time admirer of the Earthsea novels (the likes of which inspired Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind and Howl’s Moving Castle), was wholly against it, and protested the production on several occasions. Miyazaki was worried about how his son would tell the story and the emotional toll direction would have on him, which drived his attempts to undermine and impede on his son. Still, though reluctantly, it was him who went along with Suzuki to convince Earthsea‘s original writer to allow Gorō to direct, even vouching for his competence.

[In reference to Gorō Miyazaki and Tales from Earthsea]

It’s good that he made one movie. With that, he should stop.

— Hayao Miyazaki

Years later, as Gorō’s second effort, the Hayao-written From Up on Poppy Hill, commenced production, Hayao criticized the lifelessness of his son’s storyboards, commenting on the main character’s utter lack of character and requesting a change in her personality. Later on, he suggested additions to the humanity of the opening scene where she raises the flag in her backyard, describing how she should be more lively, and making suggestions for elements of her daily morning routine. Gorō would stand his ground during these conversations, but inevitably would silently consider his father’s ideas, and eventually scenes were altered to make the character’s attitude more energetic and brisk; his father managed to interfere with the production.

[During the storyboarding stage of From Up on Poppy Hill]

I think… Gorō doesn’t get it. It’s OK for him to stop directing. I think he should. He isn’t cut out for it. ‘Wanting to’ do something doesn’t mean ‘able to’. Directing isn’t an easy job. You must push yourself until your nose starts bleeding and see what you create. Most people can’t do it.

— Hayao Miyazaki

As production continued, every member of the staff gradually became more impressed with Gorō’s ability to communicate his ideas, and create consistency in between departments for what he wanted his film to be. They trusted his creative vision and worked off of his ideas, convinced that he could see the feature through to the end. Within his staff, the comparisons made between him and his father were stripped away, and he could be seen as his own filmmaker.

At the home stretch of Poppy Hill‘s production cycle, an earthquake struck Japan and a tsunami devastated Tôhoku’s coastline. Suzuki held a meeting to discuss the possibility of delaying production, but Hayao fought tooth and nail to make sure every staff member kept working, insistent that the film’s release date not be delayed. Gorō echoed this sentiment in this instance, and made sure production continued. Both men saw eye to eye, and the two encouraged staff to tough it out during the less than optimal conditions.

[In reference to Gorō as staff crunch to get Poppy Hill done in time for release]

He must lead the pack and give his all. He should be willing to die for it. He needs to finish it, no matter what. He has to do it, for his own sake. Because he chose this path.

— Hayao Miyazaki

Once momentum had been regained among every member of the staff, Miyazaki became less and less involved with the film’s production, and it seemed that by the end, Miyazaki was confident in his son’s ability to make his own art. The friction between the two was over, as was the friction between Gorō and the studio. While those who had worked on Tales from Earthsea had already been onboard with Gorō’s creativity, the positivity had now infected the entire studio, and 3 years later, Gorō was chosen to direct the series Ronja the Robber’s Daughter.

It was then in 2016 when Miyazaki found himself interested in adapting two different novels, Earwig and How Do You Live?, and when he approached Suzuki regarding his opinion, the producer suggested Gorō direct the former. Gorō had previously read Earwig, and decided to adapt the book due to his interest in its story. Toshio, Hayao, and Gorō were all entranced by the character of Earwig (Āya in Japan), fascinated by her confidence in manipulating adults to obey her demands. They thought she would bring a new flavour to the traditional Ghibli protagonist, and her unique personality drove their decision to produce the film.

Miyazaki was not nearly as involved with the production of Earwig as Gorō’s previous two features mainly due to his involvement with How Do You Live?, not because of full confidence, believing the project would be “kind of impossible for him.” According to the man’s later reactions however, he expressed great fondness for Gorō’s directorial decisions and faithful adaptation of every element of the novel. When listening to Miyazaki describe his feelings on the film, you can recognize the truthfulness in his voice, and it’s clear he has genuine respect for his son’s work.

In Miyazaki’s late age, he appears to keep a higher opinion of Gorō’s ability, and has seemingly observed legitimate improvement in the quality he is capable of. Considering his acclaim for Gorō’s skillful use of CG, he will likely have faith in his son’s future prospects, just as Gorō always had in his. Truly, this happy reconciliation between father and son finds us a happy ending to Gorō’s plight. That is, if there weren’t just one problem…

…Miyazaki was right the first time around.

Gorō should have stopped. Fuck, should he ever have stopped.

I believe everyone can be creative. Everyone has an ability to create great art deep inside them. But you need excessive practice before that point. You need to prepare yourself, gradually improving your capabilities and challenging yourself more and more. You can’t just jump straight into the highest position in filmmaking because of nepotism. Because that’s what this is, even if the elder Miyazaki wasn’t on board. I’m sure Gorō did well in architecture but… it’s because he studied that field. Architect to animator? What? Why would you do that? Even if you regretted your decision to focus on architecture, just… study animation as a hobby! Maybe try a short film! Build your way up to directing something feature-length!

Tales from Earthsea is… pretty bad. Not just bad in comparison to other Ghibli films, bad in general. It’s somehow both too slow-moving and too rushed at the same time, a paradox that was once unimaginable made real by a vastly inexperienced storyteller. It fails to capture the atmosphere of fantasy, orderly marching through the subjects and objects of fantasy without taking the extra steps to give the world the wonder it needs. It stays stoic throughout its runtime, comfortable focusing on unimaginative farming practices rather than exploring its promising world.

Though Poppy Hill is well-regarded, I find myself mostly unengaged while watching it play out its awkward teenage drama. A drama, mind you, that is only given suspense through a semi-related incest scare that drives the entire third act. Its historical basis and nostalgic mise en scène give the film character, but are wholly unconnected with the tissue of the primary story, and the far more interesting background of spirited student activism and war tragedy are left discarded in favour of melodramatic schmaltz. And it shouldn’t even have to be said that Gorō’s best film just happens to be the one where his father was most involved, with those more interesting themes likely originating from his contributions to the script.

But Earwig… well, Earwig is on a whole other level. This is well-known, of course; few on Letterboxd care much for the film, to the point where, at the time of writing, it finds itself as the 148th lowest-rated animated film on the site (which doesn’t fare well for it, if this list is any indication). At the very least, Gorō’s other films (and even the notorious Ocean Waves) managed an overall positive rating, but something about Earwig set off even the most dedicated of Ghibli fans, and I think it’s pretty clear what that thing is. The elephant in the room: the animation.

Studio Ghibli. A name synonymous with gorgeous hand-drawn animation. Maybe their stories were a little weak at times, or the ambience didn’t fully set in when it should have, or a plot thread wasn’t as well-explored as you wanted it to be, there could have been anything wrong with the film at large, but no matter what, without fail, their animation was always incredible. Even their lesser, cheaper efforts (Ocean Waves, The Cat Returns) would still be notable as being stronger work than the standard at the time (even in comparison to animation’s Western icon, Disney).

So why, why for Christ’s sake, would you change that? I’m not against change simply because it’s ‘not what it was’ (in fact, I think spicing up your formula can be a very positive thing when creating new art), but 2D animation is what Studio Ghibli’s entire infrastructure is built on. They’re a group of some of the most talented animators in the field, able to bring any image to life. It’s also what lets them stand out from the crowd; in this era where 3D is the norm worldwide, to have one of the most popular animation studios specialize in 2D is refreshing. To go against that, reject your origins that broke ground in the animation industry, and fall in line with what everyone else is doing just seems ridiculous.

But, hey, maybe it wouldn’t be so bad if the 3D animation helped Gorō tell the story, right? Maybe it’s purposeful? Maybe it represents one of the film’s themes?

No. Gorō’s motivation to use 3D was out of curiosity for the medium, it’s as arbitrary of a decision as it could get. Not only that, his curiosity to use it comes from his belief that it would be easier than 2D animation.

…a minute-long one-shot scene is extremely hard to do in hand-drawn animation, particularly if it involves detailed acting. With hand-drawn animation, you first have to get the drawing right, and these proper drawings have to seamlessly convey the detailed acting … which is very difficult. But with CG it’s possible to have different people contribute to one scene, so there is this possibility of raising the bar on the quality of the acting. That was very appealing to me.

— Gorō Miyazaki

So, his motivation was rooted in laziness, not ambition. With the studio’s 2D works, after storyboarding is done, each shot is animated by one person in rough sketches. They spend hours and hours creating a character’s emotions through the urgency of their actions, the subtlety of their expressions, and the flow of their movement, to the point where the sequence becomes personal to the animator. Not only do they have to draw expertly, they have to understand the character they’re drawing on a deep emotional level, turning the animators into actors themselves. Then it’s inked with the character’s acting intact, and for every new shot, a background is hand painted off of the angle the animator chose.

With Earwig, plastic assets are puppeteered to move from Point A to Point B, with a set of available expressions that an AI converts from one to the other. Every scene has several people manipulating and altering, with a rendered background that doesn’t have to be redrawn between different camera angles. Shortcuts are taken constantly because of the computer’s contribution. The character’s emotions are artificially designed to get a specific emotional reaction out of you. Nothing is meticulous because it can be changed later. 3D animation is plainly lazier than 2D animation, which goes almost completely against the ideals of one of the most innovative and persevering animation studios in the world.

Even still, if it looked good, perhaps I wouldn’t mind the change. If they put together an appealing artstyle that still felt Ghibli-esque with the new medium, maybe I could appreciate Gorō’s efforts to do something new. I mean, does the film look good?

I think you already know the answer to that question.

I should almost thank Earwig‘s visual shittiness for letting me communicate its abhorrence in such poetic detail. But then again, such descriptive opportunity forces me to endure that same shittiness for up to 82 minutes, so it more or less cancels itself out.

If you were to describe Earwig‘s artstyle as hideous it would be an insult to hideousness. Its synthetic non-aesthetic, coupled with awkward movement, sterile colour palette, and universally poor character design, forces you to come up with an entirely new adjective. What that adjective is may take time to discover, but I’m sure if we collected the greatest linguists, etymologists, and semanticists from all over the world, it could be found within just a few decades (friendly reminder that I opt not to engage in hyperbole, this is my most generous estimate while staying realistic).

The comparisons to inanimate dolls have already been made endlessly, but not without reason. One of the film’s major plotlines involves Earwig’s attempt to acquire a strand of her foster mother’s hair, but it’s hard to get invested in when you’re not convinced she dons anything but a hairpiece. How could the audience possibly believe there are follicles on that head? The practically untextured pseudo-flesh of each figure makes just about any style of lighting look harsh on their plastic skin, and only emphasizes how jarring the realism is on their props. How can I be engaged watching the robotic movements of a mannequin with a preset lineup of molded expressions, especially when there’s distractingly fluffy fried bread that I could be staring at?

And it certainly doesn’t help that Gorō’s direction embodies the same plasticity as the visuals. Every shot is framed like a Ghibli movie, but without the purpose a Ghibli shot should have. Every idea present in the film feels subtly derivative of ideas from the studio’s past work, but not in a way where any of them fit together very well (or at all). The grounded atmosphere of older Ghibli films feels like it’s being imitated, not successfully recreated. Nothing in this film works together to form something great, but it’s mixed anyway, stirred together in an unsightly digital cauldron and lathered upon the audience whether they like it or not.

And about the lathering… um… Gorō, what the fuck? Whether or not it was in the original novel is irrelevant, why would you keep it when it is so incredibly uncomfortable in the film? How does lathering a potion all over your body qualify as a ‘Ghibli magic’ moment to you?

It almost feels as if Gorō set out to create an uncomfortable movie considering the awkwardness of the dialogue. Every character interaction flows so incredibly unnaturally that it feels like two AIs talking to one another; simulating communication, but not quite connecting with one another. Acting the part, but not quite relating to or building off of what the other person is saying. Gorō can’t seem to deepen his characters’ dimensionality beyond the barriers of these artificial interactions, and the audiences’ immersion hinders because of it.

His characters’ unlikeability creates a different, but similarly unyielding barrier; one that deliberately focuses its efforts on deterring the audience from immersion or relatability. The main character’s motivation, throughout the film, is to manipulate those around her for her own purposes, even going as far as to describe a desire for them to obey her. Such characterization could work if she learned her lesson by the end, or if the film was a deliberate effort to call out this kind of behaviour, but instead, by the end her adopted parents surrender to her bidding, and she’s rewarded for her warped perspective and mindset.

Despite that, you don’t really feel bad for Bella Yaga or the Mandrake either because of how very abusive they are. The Mandrake is a reclusive artist who is utterly absent for the raising of Earwig, and Bella Yaga is a demanding old wench who forces a child to be her workhorse the entire runtime. Both sides of the familial dynamic are ugly and combatant, so, lacking anyone to root for in this hateful schism, you just end up hating all of them equally.

And don’t try and tell me it’s smart because it’s an allegory for capitalist exploitation (obviously that messaging is not lost on me), the film completely fumbles that one by disallowing the symbolic figure for the working class to be given any sympathy, as well as inexplicably reversing the authoritative dynamic and making the bourgeoisie live a life of servitude to the proletariat (As though the film is trying to say the exploiters have it tough because they need to take care of the exploitees? The working class are living the good life while the ruling class are breaking their backs making sure they’re not in poverty? I’d like to see what world you live in, Gorō).

If you were to give any compliment to the film, it’d be the music by Satoshi Takebe, who was also responsible for the music of From Up on Poppy Hill. My main thought while listening was that the composer must have made some video game scores beforehand, as the music is catchy and jazzy, but not fitting for the score of a film. Though it rarely matches the tone or emotion of the scene at hand, the music is truly well-written and lively (find ‘Opening’ on the soundtrack and you’ll see what I’m talking about), and far and away the strongest element of the film.

But that’s all the more unfortunate than a terrible score; the fact that the music is wasted on such material is a true shame. Talented artists worked on this film, and ultimately, it’s only one of them who is at the core of the problem. From every perspective, finding the source of the film’s various poor elements only leads back to Gorō. The aspects of this film that could have reasonably been affected by the director are universally poor, and I’m frankly not sure how anyone could effectively defend Gorō’s artistic ability at this point. His incompetence is quietly infuriating, making it difficult to give him the benefit of the doubt.

And that only fuels my pity for him further.

See, of all Gorō’s deterrents, only one hasn’t come through: the critics. Because of his shortcomings as a director, his films are berated with such an enormous amount of hate that it’s truly disheartening. The fact that I’m a participant in that hate only disheartens me further, as I wish I could see the good in his work. Alas, as far as I can tell, he only makes every project he’s apart of worse, and the hate that is directed at him (including that which I’ve now created), although not justified, certainly feels natural.

There is a perennial theme in Gorō’s narratives; that of fatherhood vacancy. In Tales from Earthsea, Arren stabs his father right out of the gate; the thoughtless anger he feels in his youth. In Poppy Hill, the most prominent plot point in the third act revolves around the main character’s dead fathers; the metaphorical illustration of absence. But in Earwig, the theme comes in its most literal form as it relates to Gorō, the Mandrake. A secluded, passionless figure, one whose art, the only source of happiness for him, takes precedence over all other aspects of life. This is how Gorō saw his father as a child; a literal demon.

Seemingly, this attitude discouraged Gorō from ever trying to reach the heights of his father, until Suzuki gave him a push in the artistic direction. At some point, Gorō decided he would try, looking up at his father’s art with awe. But it’s because of his lack of practice, his lack of experience or preparation, that caused his films to turn out the way they did. He did what all rookie artists do; saw what others were doing, and copied it. Tales from Earthsea, a limp imitation of the epics of Miyazaki, Poppy Hill, strikingly reminiscent of the grounded character studies of Takahata, and of course Earwig, a frankensteining of each of Ghibli’s old ideas and aesthetics, each one mashed together in a highly computerized industrial processor. It’s this unoriginality due to admiration, this amateur retreading of old cinematic creations, it’s this that makes the visual of Gorō’s Earwig sitting in front of the television to entrance herself in Howl’s Moving Castle far too perfectly symbolic.