Through astounding spectacle, Terry Gilliam projects his truly original, dystopian nightmares to the screen.

— Give my regards to Alison and the, er… twins.

— Triplets!

— Really? God, how time flies!

Brazil is one in a long line of many films in which the visionary who created it had the rug pulled under him when the studio that produced it decided it couldn’t be marketable. Like every film that fits the same bill, the big-wigs, in all their corporate wisdom, whittled the film down into its most bare bones structure, deleting any and all social commentary, coherence and creative wit that had been present otherwise (or so the story goes). Unlike so many of these films whose stories befit such a description however, Brazil itself is far more interesting than its production history, thanks largely in part to the darkly comic surrealist world Gilliam hastily rushes us through, a world that relies so heavily on imagination to communicate administrative mundanity, it almost feels contradictory.

There’s a reason why this film has gone down as a cult classic. Gilliam’s cinematic sense for realizing disorientation within the ever-moving synergy of business traffic and the daily humdrum of pointless bureaucratic busywork is astounding to behold and undeniably a brilliant expression of such confusion within the operations of business, a demanding affair which inevitably leads to working class ennui. Gilliam commits to this tone without disruption, belting out on an anti-establishment rhythm reminiscent of punk rock album covers. He can’t be stopped at any point in the runtime, castigating every element of a society led by a domineering bourgeoisie that he finds offensive to his sociologically-minded, populace-sympathetic philosophies.

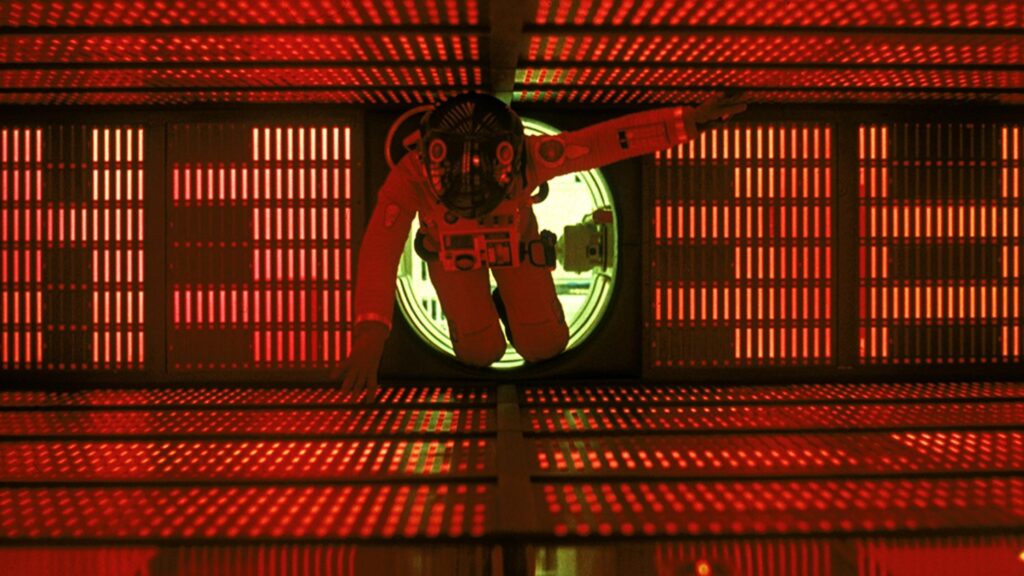

We find a tiring navigation through the bureaucratic hellscape; a watchful police state with procedurals and paperwork that actively hinder the efficacy and efficiency of their movements. It’s a system explicitly designed to be incomprehensible, its labyrinthine structure storing complex layers of constant (mis)communication, always searching for any of thousands of excuses to make an error. Any fault of the system cannot be corrected because of the continuous faults that will occur when any attempt is made to correct it, thereby making the entire order of things unbreakable. Gilliam’s pessimism (perhaps realism?) finds its foothold in the conclusion that no one person can escape the stone grip of these tyrannical authorities; at least not by vitalizing their functions.

That’s the interesting thing about total bureaucracy; because it is a constantly moving machine that remains motionless, the vast majority of tasks accomplished, or reports written, or jobs given are utterly useless. Work is completed and handed out simply because work has to be done, productivity has to be simulated, and to justify it, employees are pitted in competition with one another to ensure no one catches on; if you question the value of the work you’re performing, if you hesitate, even for a moment, you will fall behind and you will be left behind while your peers continue to move up in the machine. It is this continual effort on the part of the labourer that buries the suspended animation that comprises the institutions of the bureaucratic system, and such the effort of any motion within it.

That’s where Tuttle fails as much as any of the indoctrinated employees at the Ministry of Information; by actively fighting against this impenetrable societal organization, he legitimizes that which he despises through his great efforts to end it, and only temporarily, gives a piece of the system a genuine purpose; to terminate his irregularity. That rush of paperwork that he so eschews swirls in the wind without target or purpose, but once he comes into contact with it by attempting to destroy it, it latches itself onto him, smothering him in those gross functions of state affairs and corporate make-work. Once he has fully evaporated, consumed in his entirety by the gears of administration, the papers become directionless again, returning to their movement absent of any goal to strive towards. Gilliam posits that to truly penetrate the organization of things, you need to simply undermine it, and the only way to do that is to dissociate yourself with it entirely, rather than dancing the same endlessly mobile dance it does.

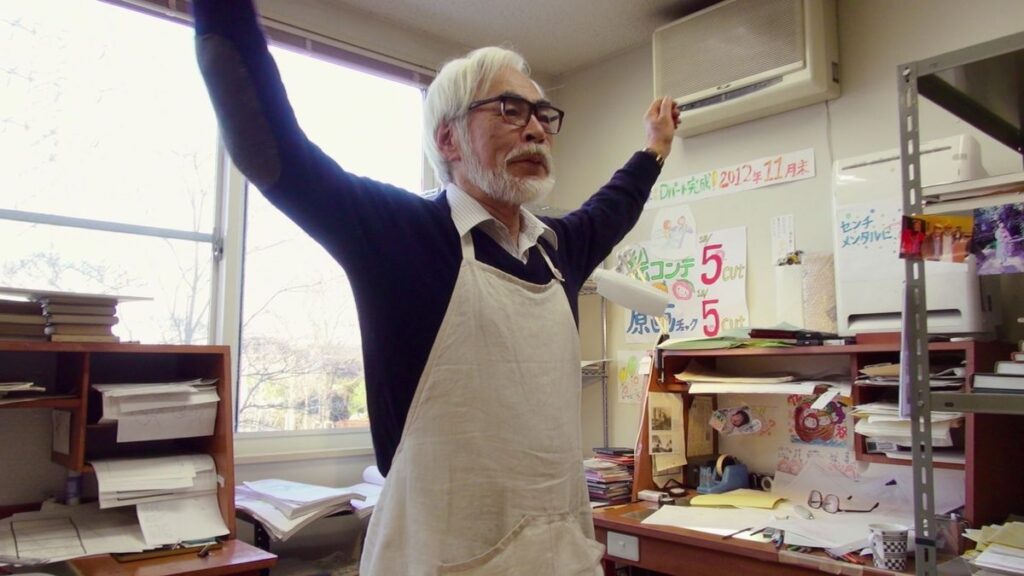

A favourite quote of mine from Hayao Miyazaki expresses a great truth about how so much art defeats itself by presenting struggles individualistically, presenting the battle between good and evil as a condensed, isolated event wherein what is identified as a righteous cause ultimately triumphs, and the singular source of oppression and hardship falls to its knees, gloriously vanquished by the heroes. He classifies it primarily as a status quo-reinforcing tool, a narrative crutch that lets audiences come away with satisfaction at the now-conquered corrupt force rather than an understanding of what systemic danger its real-life equivalent still presents. Brazil doesn’t descend into this pitfall as so many stories do, thanks mostly to the fact that the main villain of the story is the omnipresent dictatorship and the various repressive, censoring institutions that comprise it. Brazil’s ultimate struggle is one of vying for freethinking within a strictly governed totalitarian society defined by rationality, an abstract concept that can’t be brought justice with conventional progressions of storytelling; as such, Gilliam refuses to fall into those old conventions and focuses his narrative’s conflict on the broad, societal issues regarding the simultaneous dysfunctionality and rigidity of bureaucracy, and his narrative excels because of it.

Gilliam also succeeds in this way by disallowing his protagonist, a character who may in some way be perceived to be ‘on the right side’ (he isn’t exactly; he’s simply caught up in the gears of oppression both in the everyday tedium of worker exploitation and the more intense decampment as a classified terrorist), to be perfectly honourable or good. It’s quite evident in how he sees Jill, a woman quite literally gift-wrapped to him as an object of solitary fawning over. Her sudden infatuation with him comes immediately after it’s been assumed she’d been arrested, a fact that seems deconfirmed by her reappearance; it is not however, for any justification for her circumventing police abduction goes unexplained, subtly brushed over while the story resumes itself. This is Lowry deluding himself into believing his heavenly image of her after her certain execution; a coping mechanism after being infatuated with her for such a long period of time only to find her disinterested as well as forever lost. Without any earthly pleasures to emotionally subsist on at his status, he cannot live without his heavily ordained fantasies becoming real.

Neither is Lowry (until the fateful eremitism within his dream) on the right path towards total emancipation of his bureaucratic restraints. By unifying with the effortful cause of Tuttle’s group of freedom fighters, he animates the system’s operations in the same manner they do, and thus is defeated by their upheld existence. Gilliam foreshadows it all with the delightfully odd samurai battle within Lowry’s subconscious, a deliberate allusion to the attempted destruction of bureaucracy (the samurai) as self-destruction with bureaucracy’s own tools. No character is perfectly virtuous in Brazil‘s world, but there are certainly those who are far more blameworthy than others.

Petty bourgeois concerns and ruling class domination are probably the most consistent target of ridicule in regards to the film’s satire (a likelihood that is only reaffirmed by one of the film’s working titles; So That’s Why the Bourgeoisie Sucks), an implicit culprit for the society presented that Gilliam pinpoints frequently during those points where they are seen. When carnage occurs blatantly around them, their empathy is non-existent; they carry on with their banal discussions of unnatural beauty modifications and arranged relationships (even Lowry isn’t able to appreciate the weight of these ‘terrorist’ bombings until someone he loves is involved with it; his empathy is limited to a single damsel he finds himself infatuated with). They are oblivious to the foreign concept of compassion or mutual conversation, only concerned with the foundations of their own vanity.

This is a stark contrast with the visible poverty occurring in the pediment of the enormous and colourless skyscrapers, a scattered band of children unsupervised who are literally too low to enter the doors of employment or safety. They’re a grandly neglected mass within the total population that starve in the absence of welfare, celebrate terrorist capture under the thumb of government propaganda, and rest passive in the presence of violence and cruelty, a usual occurence for them. Though the majority of the populace is comprised of either proletarians or low security level Ministry labourers, the inescapable homelessness found at this abandoned societal substratum is the greatest moral crime of the private, self-interested ruling class; their bliss means an inferior’s penury.

None of this would be nearly as captivating without the brilliant craft Gilliam brings to the picture. His vision of a neon world debased and polluted with dirt, grime and scraps of paper quickly engrosses the audience more than any Blade Runner or Clockwork Orange ever could, providing a brilliant backdrop to the allegories at play. Gilliam names this the second film in a ‘Trilogy of Imagination’ (preceded by Time Bandits, followed by The Adventures of Baron Munchausen) and it’s plainly visible how it more than lives up to that title; whether it be the technicolour tuxedos and gowns showing up one another at bourgeois galas, the ridiculously compact personal transporters within grand urban areas, or the severe claustrophobia of dismal concrete offices with the least possible dimensions, his world fails to let up with its creativity at any point, their macroscopic metaphors standing proudly among the visual splendour.

Considering how accurately Gilliam reflects the hellish procedures of a world over which you have limited control, it wouldn’t be inappropriate to consider his portrayal absurdist only in a limited sense. The perpetual turmoil and confusion that necessarily befalls anyone absorbed in impersonal processes of transactions, exchanges of information, and arbitrary security are not that far off from those in Gilliam’s Brazil; the outlines of such anxiety are simply less subtle than they are in reality. Gilliam brings attention to a most insidious facet of the aggressively managerial society in which we live; the intention of this confusion. Every time-consuming report, every circumlocutory organization of roadways, and every useless busywork handout serves a purpose uniquely beneficial to the entrenched elite structures of society; to distract you from their cruelty. If it’s only a state of mind, so Gilliam concludes, pick the compassionate one.