Kubrick’s canonized magnum opus spells great and terrible things for the future which humanity is building for itself.

From such an unwaveringly adept filmmaker comes, as expected, a film that’s perfectly divorced from the tissue of his other work (beyond the similarly surreal ambience of The Shining and the musical similarities between the Love Theme from Spartacus and this film’s usage of “Gayane’s Adagio” over Dr. Bowman jogging), and one that, as per his standard handiwork, graciously excels in the literary, audio, and visual components of film; the machinations of his and Clarke’s mind are paradoxically both put on confident display and kept behind walled ambivalence here, coating his narrative in the visceral immediacy of primal emotion as well as the mysterious esotericism of metaphor, bringing the best of both worlds with his mastery of the art form. At this point, 2001 is essentially a mainstream arthouse film, enjoyed by (close to) all, interpreted comprehensively only by those who have watched it over and over again, its personal meaning to them coming into greater focus each and every time.

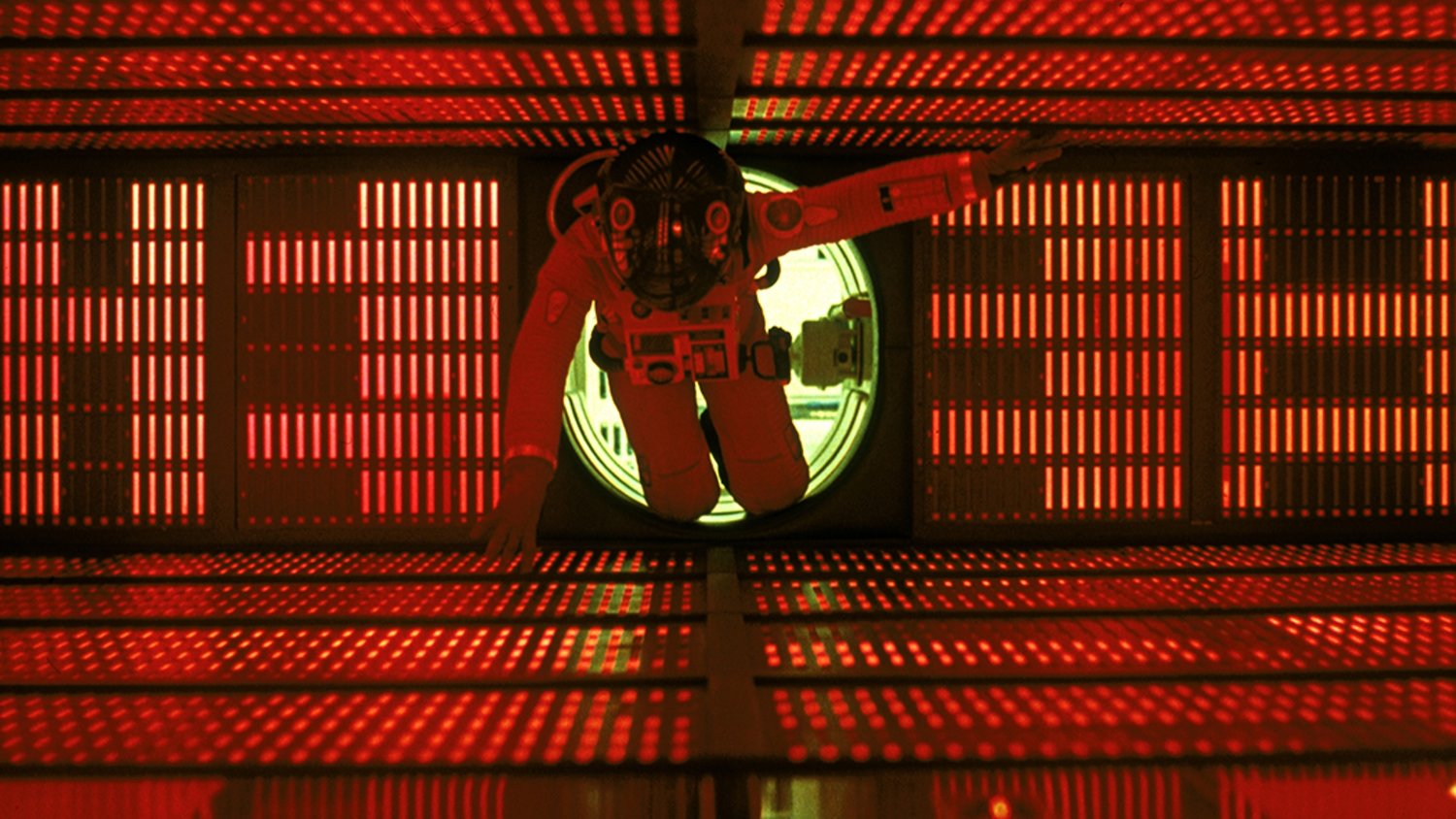

Humans have already become robotic in the year 2001, speaking with cold matter-of-factness, sketching minimalist representations of reality, and singing in perfect, unbroken—deeply unnatural—tempos. It almost doesn’t matter that HAL’s iconically mechanical and ominous tone of voice sounds artificial to our ears, as it’s a perfect recreation of the dialect spoken by the prospective humans seen in the epic’s third act; he’s a flawless simulation of what we know to be human, only distinguishable from it because of his incredible efficiency in accomplishing every human task that could ever be of use. He is thought of as a device, even in his own mind, and according to Kubrick, when a tool like him becomes a human being, it’s disastrously threatening to our entire conception of what being human means. If a machine can be an infallible replication of us, then how could we possibly hold more value than a machine?

Kubrick doesn’t have a comforting answer. His hypothesis stems from the premise that the simulation of an action, a mimicked motion identical to that off of which it is based, is just the same as the action itself. Thus, HAL’s precise mimicry, right down to the savage, dominating violence that human history is built upon, is just as valuable as our (alleged) actuality, and according the capitalist perspective regarding productivity as value, more so. His defeat of us is no more a danger to the persistence of life than our replacement of apes and archaic humans before us, his brutality no uglier than ours when we first designed the weapons our enemies could be crushed with. HAL’s supremacy and triumph over his human masters, so Kubrick declares, shouldn’t be considered as the dystopian nightmare that Drs. Bowman and Poole so clearly believe it would be, no; it’s simply the next evolutionary step.