Coppola’s detached, nihilistic opus somehow accepts the idea that American soldiers suffered the worst during the War in Vietnam.

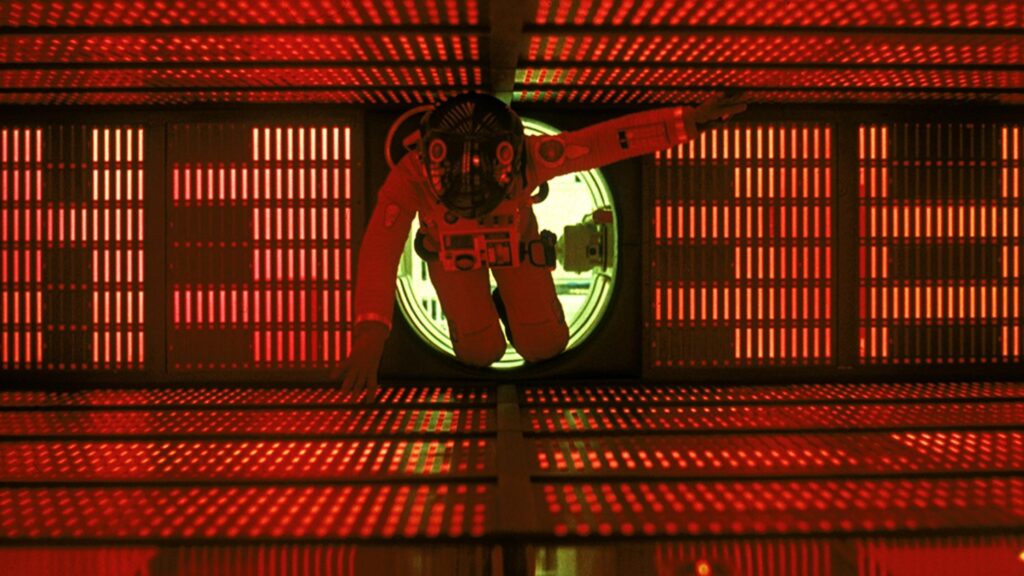

This is not an anti-war movie. It’s not even an anti-Vietnam War movie. By Francis Ford Coppola’s own admission, his film can’t be a condemnation of war when it contains “stirring scenes of helicopters attacking innocent people” — sequences “that inspire a lust for violence” and “have been used to rev up people to be warlike.” These are not only in the movie, they are its most popular moments. “Ride of the Valkyries” ignites the memory of a wartorn beachfront rushing into view, host to trees and homes set to be razed to the ground by napalm bombing. Coppola readily recognizes that films about the American military cannot truly be a protest to its existence when they traffic in the glory of its destructive power in order to produce their sublime images. I would go further to say that his film is an empty exercise in purely aesthetic greatness, a “great American novel” that doesn’t reckon with the political baggage of its American subject matter.

Apocalypse Now is a movie with no surprises — it steadily moves in a straight line towards the inevitable conclusion which its protagonist Captain Willard insists he will reach. Willard, whose narration paints him as a merciless servant to army command, is given the mission to assassinate the rogue Colonel Kurtz, played by an aging Marlon Brando, and joins a river boat in order to travel to his remote outpost in Cambodia. Willard hijacks the authority of the Chief and driver of the boat, Philips, who would prefer not to venture into increasingly dangerous territory at the expense of his patrolmen’s lives. By the end of the film, Willard’s stoic and unflinching pursuit of his mission results in Philips’ death, as well as those of all but one of the boat’s crew.

Atmosphere is more important than plot throughout this mammoth runtime. This is something to be appreciated. There is never any doubt that Willard will reach his destination and meet Kurtz (especially if you take notice of Brando’s top billing), and ultimately, the story has nowhere to go but for Kurtz to be finally, decisively killed by the man destined to be his executioner. Because of this, investing in anything other than the episodic set pieces that usher us to this finale would be a mistake. Points A and B are clearly defined, so it has to be about the journey.

Ideally, this would mean that Coppola would let us bear witness to his actual perspective. Or a more interesting one since, after all, the only profound message we’re meant to glean from this film that suffered a decade of infamous production hell is that the war wasn’t fought very well and turned out to be traumatizing for US soldiers.

A deeply apathetic mood pervades every part of this movie, as a reflection of the apathy with which the US military supposedly fought for their nation’s imperialist interests. It’s as if the whole first half of Apocalypse Now is bemoaning the unseriousness of the USA’s army of philanderers rather than the country’s imperialist aims — the inefficiency with which the pawns of American leadership pursued the goals of that leadership rather than the goals themselves. Their sheer destructive excess is far from invisible when Coppola simulates napalm strikes, or depicts the constant waste of flares and bullets, but the effect is awe, not revulsion. To skillfully portray the beauty of sheer destruction is a powerful thing to achieve as a filmmaker, but it is ultimately a manipulation.

Only a handful of human casualties are seen during that raucous “Ride of the Valkyries” firepower display. They are brief, glossed over quickly, and don’t matter. That’s fine; the movie deliberately desensitizes us to this image of an entire shoreside village being wiped out so that reality can set in an hour later, when one of the river boat’s gunners (nicknamed “Mr. Clean” and played by a teenage Laurence Fishburne) fires into a wooden boat occupied by a whole family. He does this purely as a reflex when an unarmed woman makes a sudden move. This comes across as banal, a real shame, something preventable which the men need to move on from immediately in order to press on with their mission. All of that makes sense in the army mentality, but it is also the film’s mentality given that it keeps its audience at a cool distance.

Later, Mr. Clean dies himself. In a showing of true dramatic irony, he is shot by the enemy while listening to a tape sent by his mother wishing him well and praying for his safe return home. While I may feel sorry for Fishburne’s bullet-riddled body for a moment, the feeling quickly dissipates when I remember how unapologetic he was about slaughtering innocents only minutes earlier. Hidden away in the middle of the Redux cut of the film (which I’m willing to call the best experience one could have with the movie, given that it contains the most material and doesn’t really show its length) is a sequence at a French plantation where Clean is honoured with a full military funeral. He is mourned in an official ceremony, whereas the people he killed were no more than a mistake to be dealt with in the consciences of their murderers. This is not a measure of the film’s moral complexity, but its unironic devaluation of Vietnamese lives compared to American ones.

It’s hard to agree that the massacres which took place at the hands of the United States were carried out apathetically, when their campaign of interventionism in Indochina was as rigorous and uncompromising as it always is. It’s hard to be overly sympathetic to the suffering of American soldiers when it is the disproportionately dominant obsession of America’s war narratives. I want to judge the movie on its own merits, but this proves difficult when every tragedy it depicts or discusses is only understood in terms of how it affects an operative of the oppressing nation. By the time we arrive at Kurtz’s illegal outpost (and bypass the breath of fresh air that is Dennis Hopper as a deranged photographer), his guilt over a career of bloodshed is the most that the film can muster for an acknowledgement that the tragedy lies in the deaths of human beings, not the scars of the men acting on behalf of an empire that intends to cause those deaths. This is what Apocalypse Now, a meditation on the War in Vietnam which otherwise lacks empathy for Vietnamese people entirely, just barely achieves. It does so by analyzing a soldier’s trauma.