Politics are supercharged in the director’s latest feature, but so is the dollhouse.

A weakness in cartography—the curse of the homosexual.

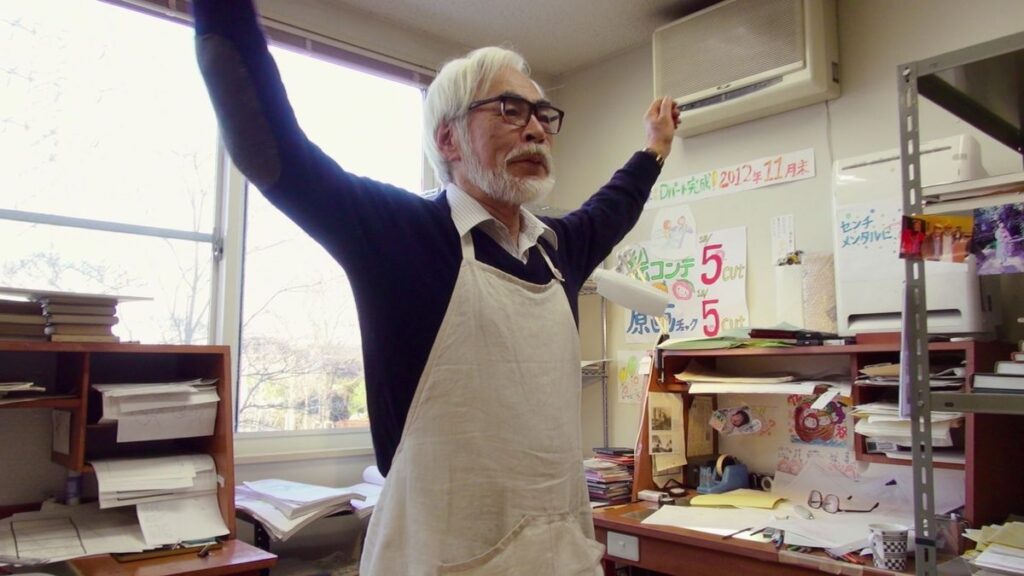

Wes Anderson’s world has always been distinctly his own, rarely succumbing to preconceived notions of cinematic storytelling, even in the presence of homage. And, after all, that’s what his films have always been: a part of a world. They’re not stories, they’re an atmosphere. A distinct aesthetic of pastel colours accented by a subtle film grain, coordinated robotic movement and monotone delivery to be disrupted only when chaos must ensue (and sometimes not even then), symmetrical framing being pushed to every possible limit of quirkiness, and visual expertise that is exquisite in its idiosyncratic artistry.

In his latest, we see an association with art and criminality, where both are treated with equal disregard, the former for its shallow essence and capitalist spirit and the latter for the basic reasons of moral wrongfulness commonly featured in bourgeois-owned media. The gag of openly mocking modern art for its artificiality is a tired one in satire, and it fails to be subverted in any way here, while the one-dimensional disdain it shows for criminals and surface level criticism it gives to revolutionaries feels like one of the cheapest ploys for status quo reinforcement I’ve seen in Western capitalist media.

Though the film reinforces these problematic bourgeois-created ideals of Western media, through such things as the portrayal of criminals as violent and unhinged (no matter how comically exaggerated), the undercutting of revolution as youthful idealism motivated by mere horniness, and respect for foreigners only for their miraculous talents as opposed to basic morals, it hardly matters in the presence of Anderson’s delightful cinematic sense. With such perfectionism in place, the humanity is already lost, so such ideals are trivial when masterful filmmaking is clearly the director’s one and only intent. I would be outraged at such messaging in an ordinary film, no matter its filmmaking qualities otherwise, but with a style such as this, it overpowers the evil.

The film introduces itself exactly as you’d expect it to. We hear a diplomatic narration, from a character who is never brought into the context of the film, describing the origins, nature, and purpose of whatever location, character, or media the title is named for (in this case, both the location and the media, The French Dispatch). Over the course of this introduction, we see our main players in the narrative (in this case the journalists), portrayed by Owen Wilson, Tilda Swinton, Frances McDormand, and Jeffrey Wright. Though one is only allowed a brief done merely for the purposes of introducing us to the anthology’s formula, each writer is nonetheless given an account or treatise to become their very own, and their own personalities prosper from the tones of the stories they tell.

Musically, the film is not as successful as Desplat’s other work for Anderson, and his compositions feel unfittingly subdued in the face of Anderson’s eccentricity. The score is far from bad, but as I am reminded of his work for Fantastic Mr. Fox and Isle of Dogs, I can’t help but be disappointed. Jarvis Cocker’s lavish cover of “Aline” steals the show by far, serving the film’s exuberant tone in the same way “Midnight Sleighride” served Isle of Dog‘s rogue adventurousness. Cocker, also the singer of “Petey’s Song” from Fantastic Mr. Fox, once again sings in performance, acting as the romanticized French vocalist Tip-Top, and his melancholic tone gives a sorrowful backdrop to the second of our three tableaus; like an experienced infatuate giving warning of heartbreak to two young lovers.

Somehow, despite understanding the Wes Anderson formula, I found myself surprised by this film’s ridiculous production value. In one scene, in which Jeffrey Wright walks down several corridors and through several rooms narrating about the building he’s in, the one-shot goes for an amazingly long time through a number of unique sets; it is truly something to behold. If The French Dispatch were to make its name as the most impressive cinematic spectacle of the year, I’d say we’d had a great year for visuals in film.

The dollhouse aspect of Andersonian production design is at its least homey here, creating locations that are gorgeously uninviting. Whether it be the noxious dejection of the concrete institution (later brought to life by del Toro’s modern art masterpiece), the grimy atmosphere of Ennui’s past, or the barren offices of a relaxedly bureaucratic dispatch, their delicate anti-beauty preserves the standard virtuosity of the architecture while simultaneously undermining it. To not deem the structural design of this film to be intricately beautiful would be to ignore the meaning of constructive beauty.

Anderson’s dry wit takes the forefront of the dialogue and his expected comedic adeptness does not disappoint. With ever-escalating back-and-forths, cutting one-liners, and an unusual amount of fourth wall nudging, hilarity seems effortless in Anderson’s writing here, exceeding the standards of modern comedy by allowing aspects of filmmaking to improve the jokes and subverting his own quirk for self-targeted satire. Unfortunately, though this excess of facetious humour is more than welcome, Anderson also makes attempts at heartfelt moments alongside it. Though Anderson is well known for success in this area, when it comes to an anthology, our characters have not been nearly as developed as those in his past work, so the emotion falls flat. Even the employees of The French Dispatch, the touchstone from which the anthology is built off of, fail to bring about any kind of empathy from the viewer (thanks to their absurdly limited screen time).

Additionally, Anderson’s trademark expository monologues occur in such surplus and at such a rapid pace, they essentially forfeit all meaning. The viewer’s experience goes virtually unaffected by the actual information in these scenes, and they’re essentially included solely because they’re a part of the Wes Anderson experience. Whatever is communicated in such scenes has truly become obsolete at this point, and the director knows it just as well as the audience does.

However, all hope is not lost. Connections can be made on a philosophical level, mainly from the musings of one Roebuck Wright, who, throughout the final article, asks questions pertinent to humanity and art. When confronted about why a great portion of his writing describes food so decoratively, he responds with a cold reserve, distracting from the question and guiding the discussion to the very unanswerability of ‘why’ questions. Why is anyone interested in the art they’re interested in? How can anyone know why they take such interest in it?

This appears to be the least crowd-pleasing of Anderson’s modern work, with prolonged displays of nudity, visceral yet humourous audible violence, and constant indulgence in offbeat auteurism: how could all of it not have delighted me. I’ve never been one for the censorship and monotony that pleases the crowd (nor censorship and monotony in their own right), so to view a mainstream film that not only maintains a creative vision, but one that embraces visuals that commonly fall under vulgarity, is refreshing.

Underneath the direction that finds itself being some of the most befitting of the Wes Anderson label, we also see some proficient performances worthy of occuring in a Wes Anderson film. Particular standouts are Tilda Swinton, whose accent is so successful that it takes a moment to realize that she’s the one portraying the character, Benicio del Toro, whose take on the depressed and disturbed artist is one that falls satirically into knowing cliché, Jeffrey Wright, who captivates during anecdotes with his natural-born narrator’s voice, and Adrian Brody, who continues to embody the spirit of the narcissistic material man pushed just slightly out of his comfort zone. Most of this all-star cast ends up playing bit parts (even Anderson veterans like Jason Schwartzman and Willem DaFoe), however each one does just enough to allow their fleeting moments to stand out among a crowd.

Though the idea of a Wes Anderson anthology was a risky one, the director secures a success from this rarely executed storytelling method. His fancifulness shines through as extravagantly and excessively as you’d want it too, and we see the acclaimed artist comfortable sincerely expressing everything he loves about this vivid European setting, and the written word itself. Every meticulous detail of this fine journalistic world is exclusively beneficial to the experience, and it is clear Anderson hasn’t lost his spark just yet. It’s unfortunate that such a unique voice in mainstream cinema is an anomaly, but his voice is well-appreciated nonetheless. Anderson delivers with this well-constructed wonder, and his world remains substantively intact.