Anti-capitalist media made by capitalists may ultimately serve capitalism, but this series undoubtedly raises the right questions.

Streaming television’s flavour of the month, Squid Game, is one international hit that most assuredly surprised just about everyone at its sheer popularity. As any overnight success in modern day, it has been lauded, condemned and aggressively memed since release. Gaining the status of Netflix’s largest series launch in history, it’s certain that everyone’s favourite corporate streaming giant is ecstatic about such a bombastic response. Luckily, this internet blow-out is one of the more substantive, a frantic horrorshow that excites and surprises with its intriguing concept, supplementing its thrills with a charitable dose of unsubtle but well-considered social commentary.

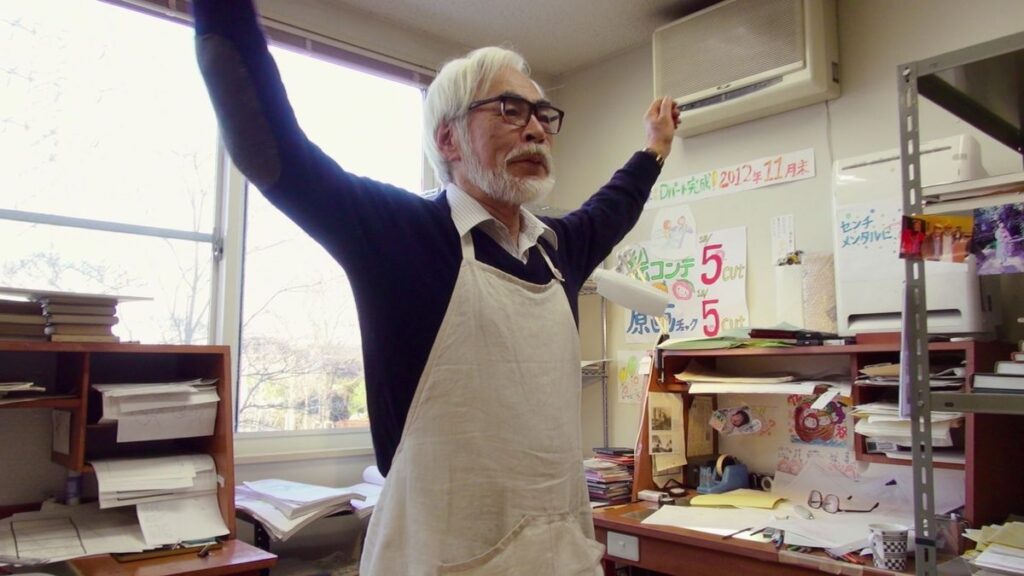

The look of the operation in which these games function is branded with creativity through the series’ inspired art direction; on its own, the production design gives off a sense of contradictory friendliness, existing to be representative of corporation’s and government’s exceedingly pristine and gentle image, hiding its psychopathy underneath. Its systematically stylised costumes, designed by the infamous Cho Sang-kyung (Oldboy, The Host, Handmaiden), are colourful, equally contradictory depictions of assembly line clothing; Seussian criticism on the facade of efficient labour being a joyful, vivacious experience and an understanding of its misanthropic, spirit-breaking creation of apathy.

Though the metaphor isn’t exactly one of the deepest or most nuanced you’ll see in media, it’s one that can certainly be considered accurate enough in its lack of complexity. Interpretations are abundant, generating an adaptability of the film’s themes to many aspects of society. Preventing mutual success and encouraging competitiveness among your mass could be applied to academia, or climbing the corporate ladder as a societal goal. The very game is clearly a metaphor for the conditions placed upon the working class that marginalize and devastate their own ability to survive.

One topic that is illustrated is particularly interesting; Mi-nyeo’s success by associating with Deok-su is an obvious allegory for the advantages a capitalist society gives to men. Society encourages women to be romantically involved with a man in order to be mutually successful with him. The women that refuse to do the same (Say-byeok) are at a disadvantage, and it becomes more difficult for them to succeed in the same way as men or married women.

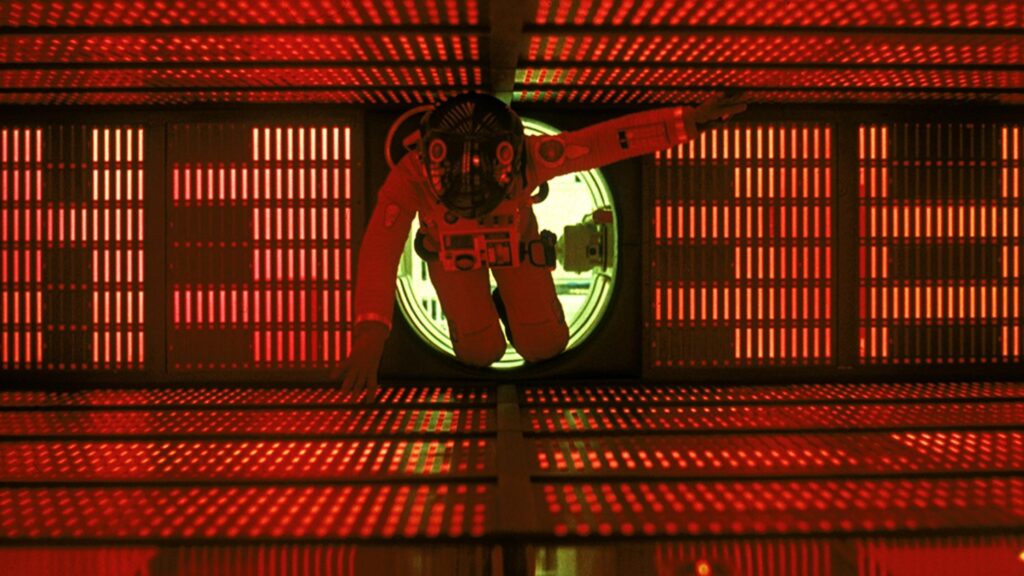

The concept of capitalist success as an illusion upholded by our surveyors to distract from the collective’s ability to uprise and improve their conditions is represented by the depravity that overcomes the participants when their context is pushed outside the status quo and a goal is placed in front of them, daring them to reach for it; an ability to murder for selfish gain (the series understands Gi-hun’s success is a fantasy in a real-world context but highlights the inhumane consequences of his victory; even if you could advance, such advancement would require selfishness). The inevitable impoverishment of the working class is represented by, well, the death of 99% of the contestants. Jun-ho’s inability to overcome the rigid systems of the game on his own criticizes individualism. All of these ideas and more are explored adequately and interestingly, manifesting an informed rage at capitalist systems, critiquing them by demonstrating them exactly as they exist; the only difference is the concentration of these ideas into one easy-to-swallow pill. By representing these ideas in an absurd and violent thriller, it makes the average ill-informed audience member (teenagers) begin to understand the realities found in its subtext.

Some elements of the narrative feel contradictory to its goals, such as Gi-hun’s portrayal as a freeloader off his elderly mother, and as a self-destructive spender of the money he hasn’t earned. If the intention is to show sympathy for the lower class and to condemn the systems that lead to their situation, why must we be given a main character who seemingly brought himself into this situation? Sure, capitalist society certainly plays a part in encouraging such behaviours, but wouldn’t a protagonist with more potential for sympathy (one who is clearly shown to be a victim of unfair conditions) make for a more successful expression of the intended themes?

As corny and as predictable as the series often is, it works well for a narrative that is already fairly simple. In spite of the transparency of its narrative conventions, it doesn’t overpower the message that is delivered. The fact that such themes are being communicated in a worldwide sensation bears well for the political understanding of the younger generation. It teaches not a blind finger-pointing at individuals who’ve supposedly corrupted our otherwise fair society (as most political teenagers seem to think), but the truth that the systems in place are fundamentally corrupt. The story is not deep, but the metaphor is brilliant. Squid Game is one (admittedly, overhyped) sensation that is well-worth viewing and very deserving of its 15 minutes of fame.