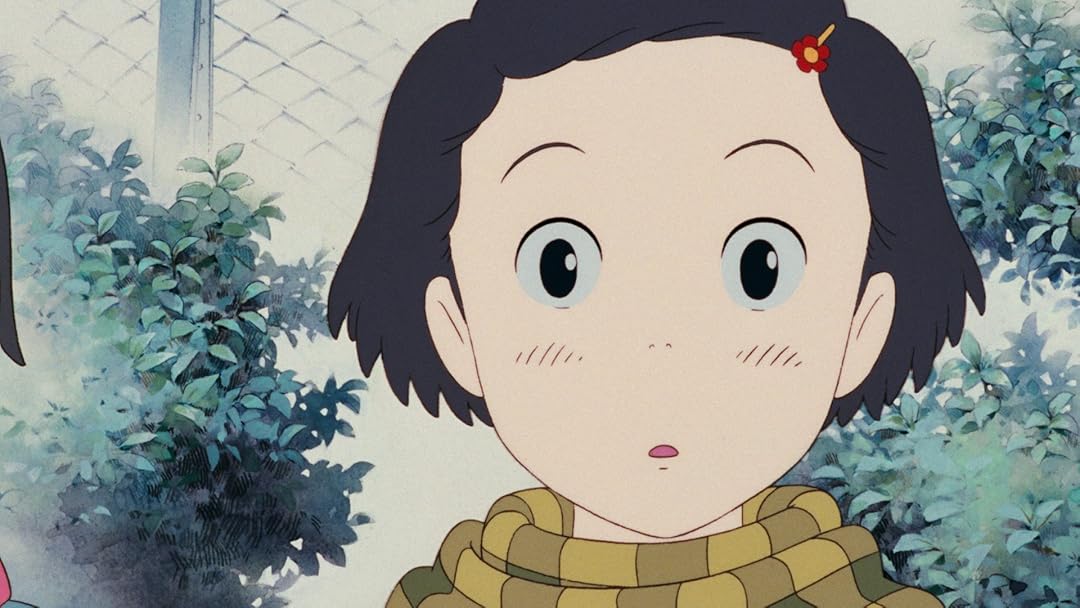

Unless you are constantly riveted by the plot of your everyday life, Isao Takahata’s intimate film will remind you of yourself.

Only Yesterday is an exercise in mundanity; an exploration of life at its most boring, for those prolonged stretches of time where nothing interesting seems to be happening is exactly what life is most of the time. Takahata teaches us that conforming to the societal expectation of what life should be creates not sadness, but apathy. As such, few realize the underlying cause of their lack of emotion and simply go with the flow, swept away to wherever society deems them useful.

In a household where the residents usually simply follow routine, eating the same old Japanese food they’ve eaten all their lives, the purchase of any fruit that’s even slightly exotic, like a pineapple, becomes an exciting family event. And when their high expectation isn’t met, the following disappointment is even more soul-crushing than it would be otherwise; because of the horror that those pleasures you haven’t experienced are equally as bland as those you have.

Taeko learns that living a bland life as an office worker doesn’t spark any kind of joy or meaningful experience, nor does the escapism of the farm; as it is simply a man-made ideal construct. To be happy is a balancing act between living in the inescapable, emotionally repressive culture of industrial society and spending time doing the things you enjoy, not living in a fantasy of what others have (‘play-farming’, as Taeko puts it).

Takahata’s ability to spin everyday actions and conversations into something deeply interesting and meaningful is nothing short of masterful. The late animator breathes personality into each character, communicating a grounded realism that feels tangible and familiar. By comforting us with this familiarity, relatability is realized, and from this, a genuine concern and caring for the characters onscreen. He allows his audience to, quite tangibly, feel (or at least understand) exactly what those onscreen are feeling, something that is nearly impossible in any art form.