Damien Chazelle’s distressing two-hander is an effective study in how to destroy your life piece by piece while grasping onto delusion.

Okay, I’m going to just lay it out. This is why I don’t think that we should be together. And I’ve thought about it a lot, and this is what’s gonna happen. I’m gonna keep pursuing what I’m pursuing, and because I’m doing that, it’s gonna take up more and more of my time, and I’m not going to be able to spend as much time with you. And even when I do spend time with you, I’m gonna be thinking about drumming, and I’m gonna be thinking about jazz music and my charts and all that and because of that, you’re gonna start to resent me. And you’re gonna tell me to ease up on the drumming, spend more time with you because you’re not feeling important. And I’m not gonna be able to do that. And really, I’m gonna start to resent you for even asking me to stop drumming. And we’re just gonna start to hate each other. And it’s gonna get very… it’s gonna be ugly, and so for those reasons, I’d rather just, you know, break it off clean… because I wanna be great.

The movies present us with a lot of men. If you don’t expand your horizons enough, you run the risk of exposing yourself only to the narrow band of popular cinematic voices that see men as characters of inherent interest and women as their supports from underneath — subordinate by narrative presumption.

Whiplash, arguably the most universally praised classic of modern American movies (and the inspiration behind some of the least interesting video essays of all time), does not defy this presumption, but calcifies it as a part of its overarching examination of artists who hold greatness to be the highest moral pursuit of their lives. Damien Chazelle spotlights their delusion, in which “greatness” is a tangible, attainable state not measured by personal well-being or even cultural cachet, but by the objective verdicts of prestigious music competitions. These are dreamers who are hypnotized by the immortal reputations of those who have mastered their craft, who can only imagine themselves atop the same pedestal, having taken the fast track to their version of “success”. Andrew Neiman is one such dreamer, the symbol of self-destructive ambition in this tragedy, and it’s him who demeaningly breaks up with his girlfriend Nicole as soon as she becomes a potential obstacle to his plans.

Andrew and Nicole’s relationship is not a key part of this movie; there are maybe six scenes dedicated to it, and one of those — the only mention it gets between their first date and eventual breakup — is a text message that Andrew doesn’t answer because he’s too busy watching videos of Buddy Rich on his phone. But its tangential presence in the film, and its efficiency at making Andrew seem like a myopic prick who cares very little for the people around him, hammers it home that his slavish commitment to this singular pursuit dissolves the potential for any human connection which does not directly advance him as a musician.

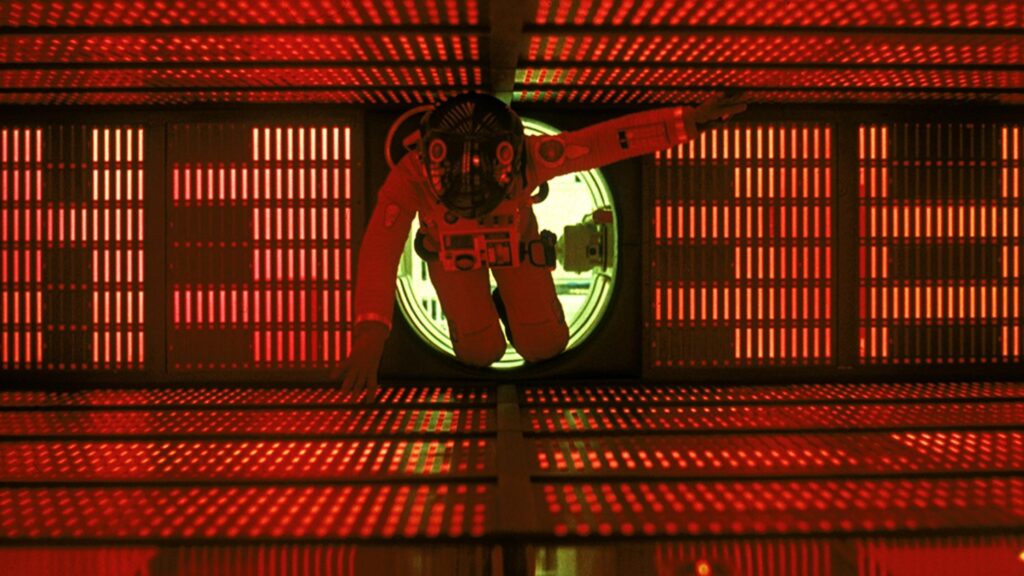

His relentlessness is what leaves him so susceptible to the abusive drill instruction of Terence Fletcher, an iconically evil anti-mentor whose dour Studio Band rehearsals summon the film’s hateful orange palettes. Fletcher’s personally selected crop of students are, not coincidentally, all male. We essentially find out why when he briefly auditions members of the lower-tier ensemble which Andrew’s initially a part of, and he immediately quips that a student in the first chair must be there just because she’s cute. He counts her in, she loses tempo, and he cuts her off: “Yep, that’s why.”

A common critique of Whiplash is that it has nothing to do with actual music conservatories or how they function, that there is no life to the ensembles, no creativity, no community — just theory and technique, rotely practiced to no end, like high school sports, until they either win or don’t. Missing from that critique is that the film never pretends that the attitudes of Andrew or Fletcher have anything to do with real jazz. Never mind whether the way Fletcher teaches could realistically occur or not (my money’s on ‘not’, but the issue is unimportant in the first place when Chazelle’s movie is so openly over-the-top), but a story about such a deliriously driven musician as Andrew who never even once shows an interest in collaborating with other musicians is clearly not a story presenting how talented musicians try and fail, but one which illustrates someone going about his craft the wrong way from the outset. His narrow commitment to success is what commits him to failure.

Whiplash depicts two men so psychotically deluded, and so convinced of an ethos based on a fictionalized Jo Jones story, that they cannot even recognize that their music (or rather, their playing of others’ music) is unexceptional. Highly listenable and soundtrack-worthy, no doubt — perhaps even one of my favourite film scores of all time — but ultimately on par with the music institutions which surround them. Just on par. This comes across no better than when Fletcher is playing at the club and his listless onstage sound, although ambient and memorable, is simply unspecial. In spite of his pretensions, he’s just another session player.

In the screenplay for Whiplash, there is a small detail in the final sequence omitted from the film. After Andrew is sabotaged by Fletcher at the jazz festival, he squints into the audience and spots none other than Nicole, sitting front row with her boyfriend. She is there to witness his humiliation, but the implication is that she would also see his fleeting triumph. The final movie wisely does not include her, handing the character some self-respect. No healthy person would waste any more of their time supplying these doomed narcissists with their undervalued attention.